By Dylan Idleman, Bud Fisher, and Connor Quiet

Introduction

Images that depict masculinity during Japan’s Jomon (c. 14,000–300 BCE) to Heian (794–1185 CE) periods capture a complex evolution in the ideals and expressions of male identity, influenced by shifting social and political landscapes. In this era, masculinity was shaped by the contrasting demands of war and peace and by Japan’s gradual transition from tribal societies to organized governance under imperial rule. Early depictions from the Jomon period, primarily found in clay figurines known as *dogu*, reflect a form of masculinity linked closely to nature and spiritual practices, highlighting robust physiques and stylized features thought to convey protection, fertility, and supernatural power. These images embody the strength and resilience needed to thrive in a world governed by natural forces without the hierarchical structures that would later influence Japanese society.

In the following Yayoi (c. 300 BCE–300 CE) and Kofun (c. 300–538 CE) periods, however, Japan’s increasing focus on agriculture, land control, and military organization began to redefine masculinity. Visual art from this time reveals a shift towards a martial ideal, emphasizing warrior-like attributes, with representations of men as armored figures or clan leaders adorned with symbols of power, such as swords and helmets. These artifacts indicate a growing association between masculinity and the roles of protector and ruler, as men were expected to defend their clans and engage in territorial conquests. By the Heian period, Japan’s warrior class was fully established. Yet, the courtly culture of this era introduced a duality to masculinity: the valorization of the refined, cultured gentleman and the martial prowess of the warrior. In artwork and literature, male figures are depicted not only in armor and with weapons but also as poets, scholars, and courtiers, embodying ideals of elegance, sensitivity, and intellect.

Throughout these periods, images of masculinity in times of war emphasize physical strength, courage, and loyalty to one’s clan. In contrast, those in times of peace celebrate cultural sophistication and spiritual introspection. Together, these depictions provide a layered understanding of what it meant to be a man in ancient Japan, reflecting how ideals of masculinity adapted to the dual demands of a society that oscillated between states of peace and conflict.

Early Period

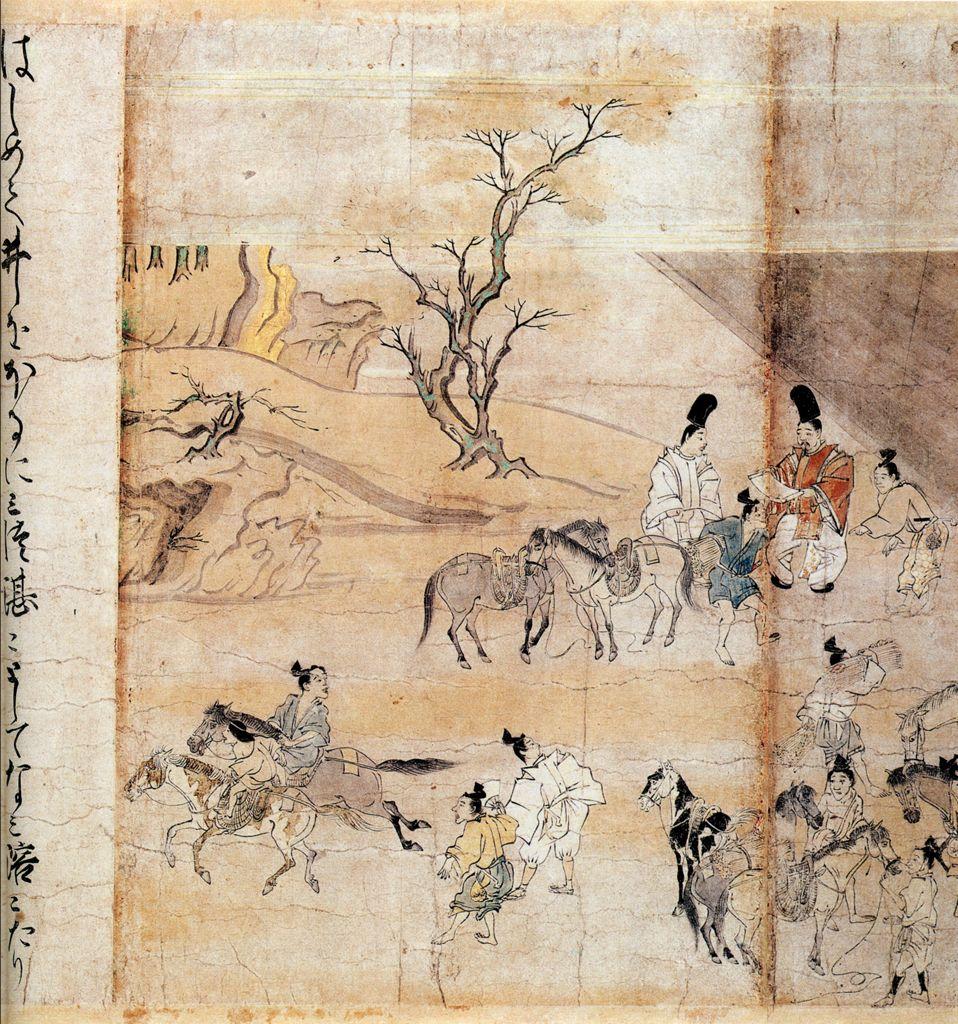

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13584267, Ban-dainagon-ekotoba (police escorting criminal) Bud Fisher

The first painting from the Heian period, painted in ink on paper, highlights men on horseback with weapons and armor. It is unclear if the men are riding through battle or out of battle, but at their feet, they are surrounded by men who are not on horseback. The men on the horses wear decorated armor which is accurate for the era, and along their backs, they carry quivers of arrows. Along with arrows and bows they have swords, spears, and knives of some kind. Although the painting is not the most clear after hundreds of years of wear, it does show immense detail which allows the viewer to pick up on how intricate the artist intended the image to be. The most impressive part of the armor is the color which is within it. As for the formation of the men on horseback, it seems as though they are surrounded by people who are not on horseback. This is only apparent because there are no standing men within the middle of the circle of the horse riders. The title of the painting adds more detail: “Police escorting criminals”. The image does not make it clear who the criminal is, but this gives more ideas as to who these men are.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14370133, scroll titled Taima Mandara, Bud Fisher

The second image that I chose shows a field, cows, a lone tree, and many horses. Although not all the men are on horseback, some are and they look like they are riding away fast. This could be the image of two men stealing horses from farmers. Just behind these horses riding away, two larger men look to be dealing with the owners of the horses. Dressed in robes, adorned with big black hats, and much larger in size than the others, they show a level of wealth which the others do not. Their robes go down to the ground, and they are in red and white which is not what the others are wearing. The land in the area looks to be dead and dry, as the tree is in the same condition and everything is brown. The group of horses to the side looks like they are being fed, and maybe this is a scene where the owners of the horses are selling to noblemen. In a time when there is not much farming going on, it seems as though maybe they are trying to take advantage of what they have. This is how the stealing people of the horses may be intertwined and the rich men are showing inequality.

Chinzei Hachirō Tametomo with two islanders on the beach at Ashijima: https://login.ezproxy.trincoll.edu/login?url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.15026742 , Dylan Idleman

This picture is from the early Heian period and depicts what appears to be an important samurai patrolling the beach of Ashijima. Based on the location of the island and its size in the context of Japan, the samurai here may be scouting. The locals look unruly and unkempt, appearing more akin to barbarians than civilized people. They look like they are listening to what the warrior commands through his body language; in the picture, he is silent and stoic. In contrast to the islanders, the samurai is well-kept and confident in his appearance. This portrayal demonstrates his masculinity as an essential figure in Japanese society. What also struck me when looking at this image is the armor, precisely the bright colors and intricacy in the design. The detail and craftsmanship that went into it further bring out the samurai’s character. In the contrast between the scantily clad islanders and the elegant Tametomo, the feeling of superiority is elicited through the image. The towering presence of the bow that splits the scene between the islanders and the samurai is crucial in furthering a powerful contrast that contributes to the masculinity of the samurai. Now, it is interesting to wonder whether this image represents a warring environment, and the fact the samurai ventured out to this little island may suggest that he was scouting for combat or simply going out to establish new relationships. The mystery of it keeps the meaning ambiguous, but not to a fault.

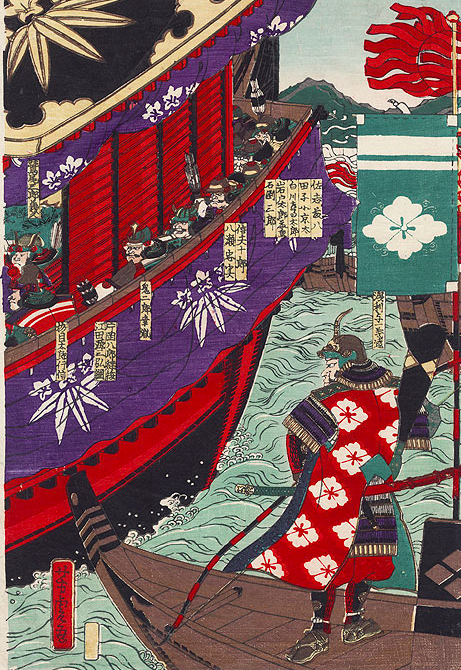

Japanese Woodblock Print: The Genpei War, Dylan Idleman

This second painting I have chosen to add to my virtual museum is a different art style, while also depicting a scene from the Genpei war. While the Genpei War was set during the Heian period (794-1185), this style of painting didn’t come about until the 1800s. This particular painting, a Japanese woodblock painting of the Genpei War, was created by Yoshitora (1840-1880). In this painting, you see very vibrant colors, allowing these warriors, also known as samurai, to stick out from the rest of the painting. These types of paintings perfectly highlight the masculinity and prestige of these warriors, from the large figure they hold to the detailed and intimidating battle armor they wear, paying homage to those they are fighting for. One key distinction in this image that points to the type of warfare that was taking place in this time period is the bow that is bounded by the main figure, or warrior, standing tall on a small boat or canoe. Firearm use during the time of the Genpei war was not as common, and most of these armies were formed of cavalry, warriors on horseback, and often using archery as the preferred method of warfare. This image perfectly captures the entity that was the Genpei War, and while it is quite the contrast to the other image I have chosen, they both highlight the key features that hold the Genpei War’s history in the roots of Japan.

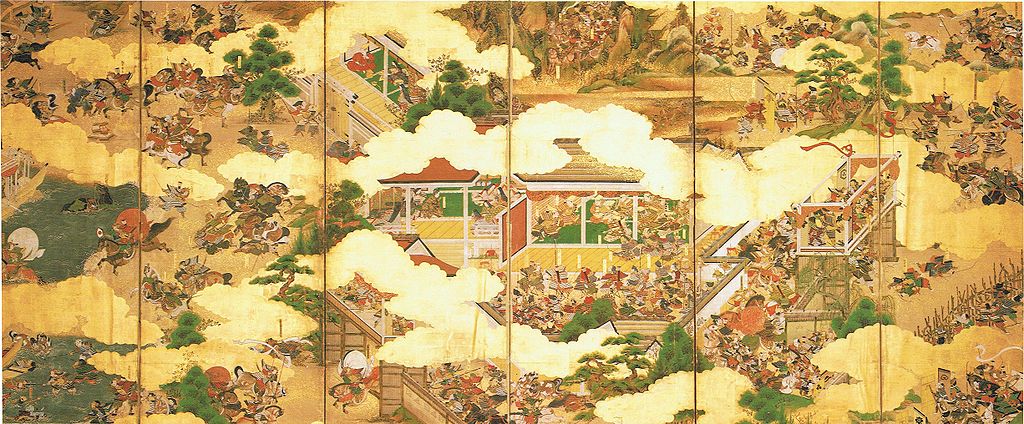

Genpei War Scene by Kano Motonobu, Connor Quiet

This is the first painting I have chosen as my first part of my museum exhibit. This is the Genpei Battle Screen, depicting a scene from the Genpei War. This painting details a wide variety of combat between enemies, and civilians caught in the crossfire. In the bottom left of the artwork, you will find soldiers marching into battle in complete unison, showing their professionalism in order to place fear into the enemy. A complete contrast to that happens in the far right hand side of the artwork, where soldiers are much less orderly. These warriors are on horseback, and appear to be the frontmen of the warriors marching on the left side of the artwork, as I previously. I interpret the cloud-like shapes to be smoke, as the charging cavalry presumably ignited as much of the village on fire as possible when making their original ploy. Connecting to the overall theme of our museum, this piece of artwork is a wonderful depiction of masculinity in war, as the majority of these warriors (I would assume) are men. This points to the overall gender roles that took place during the Heian period, and how the role of protection and domination was given to the men, boosted into the warrior mindset. This full-scale, wide ranging painting depicting the Genpei War encapsulated the full aspect of war: the powerful and the weak, the good and the bad, and brave and the honorable.

Minamoto no Ushiwakamaru battling with Kumasaka Chōhan: https://login.ezproxy.trincoll.edu/login?url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.15051352, Connor Quiet

This is another depiction from the early Heian period by the same artist, Yoshitoshi. However, this one is quite different from the previous one as this is an active battle between two combatants. The age difference between the two fighters stood out first and may be the most important in breaking down this image. The one in red with dark black hair signifies his youth, at least in comparison to the other. The samurai in green has the slightly noticeable detail of a grey beard. He, a hardened warrior, has already proven his worth and masculinity, whereas the younger has yet to be as established. Immediately, there is a dynamic of experience versus aspiration. Another noticeable distinction is within the outfits that the two combatants adorn. The older samurai wears green armor, which comes to mind when considering traditional samurai armor. In contrast, the younger samurai has red robes that look as though they provide fluid movement. The red gives an image of aggression in fighting style and the lack of protection. The difference in weapons further delves into this theory as our red-clad warrior wields a katana, which is meant for closer and quicker combat than a naginata. Ultimately, this battle of will versus attrition is exceptionally provocative in its imagery.

Medieval Japan

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.18571859, Portrait of a Warrior, Bud Fisher

In this painting, it is clear that the soldier or warrior is of some importance as he is the only subject of the piece of art. In his robes, on a mat with his sword, he seems to be looking off into the distance. This could indicate some sort of thought, but I’m not sure what the artist intended. The robes are not extremely detailed but may have some marker of rank or allegiance on the chest, and he seems to be an older man in the painting. The sword that he clutches is black and adorned with gold, but does not look like it would be his full-sized sword. The outside of the painting is outlined with gold, green, white, and red. This very simple painting is different from what was created before of warriors. This is much more simplistic and represents a more informal warrior. If his sword was not present, this could be mistaken for a normal man, but the causal nature of the painting seems to represent that the warrior class was not as important anymore. Although there is no indication of war, this warrior seems to be in a time of peace considering his lack of armor and weapons. This could be an indication of the political times during the era although this was painted around 1500. This could be a clue to the paintings we could have looked at before and how they showed the political climate of the era.

Night Attack on the Sanjo Palace, from the Illustrated Scrolls of the Ev: https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.15628473, Dylan Idleman

The image depicts the rebellion that occurred at the end of the Heian period between disgruntled court advisors from the Fujiwara clan. However, the art itself was made later during the Kamakura shogunate, which was experiencing the effects of this conflict, which is reflected in the artwork itself. We see a ferocious assault from the samurai, who employ many devastating tactics. It looks like they are in a palace where orange flames are beginning to engulf the surrounding area. This is important in how this piece stands out from other depictions of battle and war because the usage of fire is not something commonly seen in art. It makes me wonder if that reflects the masculinity and pride of the samurai in war. These scorched earth tactics may be looked down upon societally, making this work of art unique in showing the reality of war. This is a one-sided battle as it was a surprise attack, with nearly all the samurai in the assault wearing similar greenish armor, with one standalone that appears yellow. The lone warrior is battered and one of the few we can see with blood running down his body. This opens up another theory in which there may be conflicted reasons for creating this work of art. It may show the bravery of the last man standing against an unpredicted assault. However, his face is not shown, which makes this a shaky theory. The instability of the Kamakura period produced this work of art to show the savagery of war.

Onin War by Utagawa Yoshitora, Connor Quiet

This second image I have added to my online exhibit is a visual of the Onin War, depicted by Utagawa Yoshitora (1852). As opposed to my earlier visual entries, we are able to see a much more prominent Samurai presence in this battle scene. With the Onin war came the start of “samurai culture” as it took off across Japan, much further than the battlefield. In this visual, the armor worn by warriors is much more pronounced, whereas the visuals from my previous entries showed soldiers wearing similar uniforms, as if to signify unity. With the new era of samurai, warriors were actually rewarded individually based on their statistics from the battlefield, yet another reason why we see a shift towards individualized battle armor and glorification of battlefield status. You can see their green armor, which is similarly represented among most soldiers, as a form of unity. But, in contrast to that, many of the warriors in this painting don very sophisticated helmets, which is a direct signal to their “warrior status” among other Samurai. This visual is certainly an all out war scene, which is very accurate for this time period in Japan. As written about in my midterm essay, the Onin War is a significant part of the warring states era of Japanese history, as it was a very bloody era, as accurately depicted in this visual.

Early Modern Period

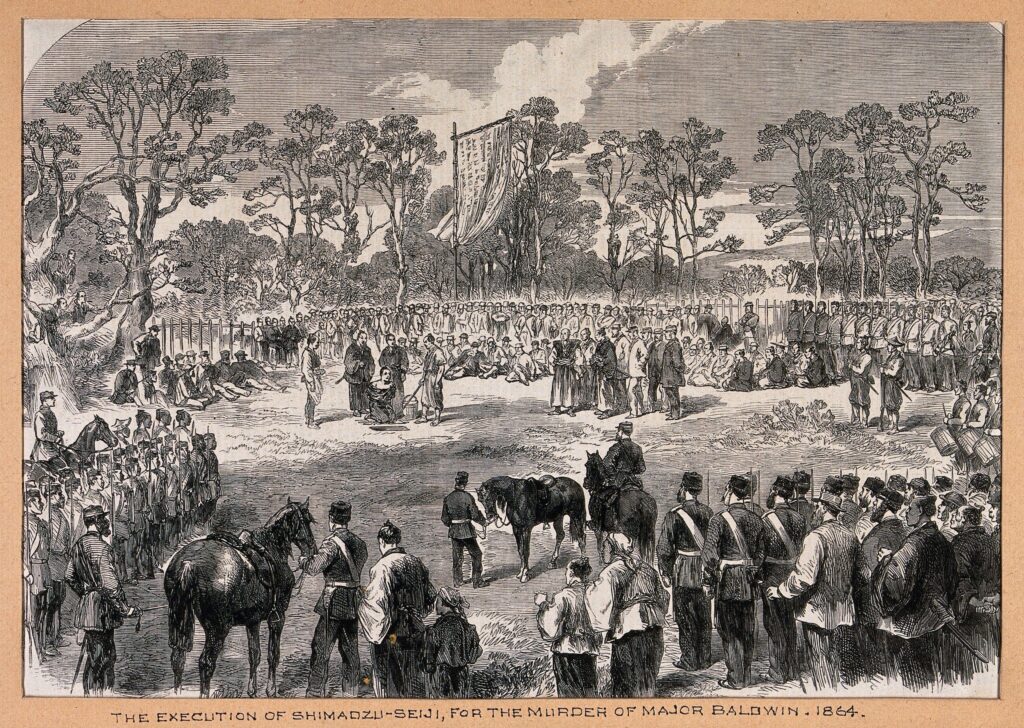

The beheading of Shimazu-Seiji in the “Satsuma War”, Japan 1864. Wood engraving, 1865, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.24887244, Bud Fisher

This wood engraving from 1865 exemplifies the beheading of Shimazu-Seiji in the Satsuma War. The piece of art is in black and white and is impressively carved with lots of detail. The picture shows hundreds of people in a circle. All in uniform, some horses and soldiers seem to gather around to see a ceremonial beheading of someone who I can only assume is either an enemy or a traitor to the army. There is some sort of sign banner above the man being beheaded. This could read his crimes, or who he was, but this is left up to interpretation. The dark format of the art conveys the message of a sad scene. The uniforms of the soldiers also show that this is a meaningful event, and might be a clue to who this person is. The trees in the background are very detailed, and the clearing where the ceremony is going on seems to show that this action might not have been planned. The field seems to show that this could be during a military movement. Overall, the soldiers look to be dressed in American civil war era clothes using similar gear. This could show that Western influence had already reached Japan at that time. The painting shows a moment in time, that may not have been extremely important but displays a plethora of details that are important to the modern history of Japan.

Tokugawa Ieyasu Examining the Head of Katsutoshi at the Battle of Osaka Castle: https://jstor.org/stable/community.15043774. , Dylan Idleman

The image above was created at the end of the Tokugawa period, but it depicts the aftermath of battles from the early Tokugawa period. The Siege of Osaka took place in 1615 and saw the destruction of the Toyotomi clan. The interpretation of this event is rather graphically shown, with the bloodied head of Katsutoshi catching the eye immediately. It is a rather emasculating action already, but now fully displayed in print, it only further tarnishes the masculinity of the fallen warrior. In contrast, the presenter of the head kneels proudly, demonstrating his strength and prowess on the battlefield. All his fellow samurai appear stunned at the head that lays before them, but not because of lack of exposure to the cruelty of war, but due to the feat of defeating this particular warrior. Clues would lead one to guess that the presenting samurai took down a notable enemy that would significantly increase the reputation of the slayer. Another noteworthy point to take away from the picture is the building ablaze in the back left corner. One could assume that it was Osaka Castle or a part of it in the aftermath of the attack. The attacking samurai have put distance between them and the building, confident that their raid has succeeded and proved their power and masculinity in battle.

Battle of Honnoji by Utagawa Yoshimori (Museum of Fine Arts Boston) Connor Quiet

The early modern period of Japan consisted of wars by the Shōgitai troops fighting against the imperial troops. This specific battle, depicted here in this painting, was the battle of Honnoji, which was a battle that took place in the Boshin War. This painting was orchestrated by Utagawa Yoshimori (1830–1884), and this painting is actually held in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, if anyone ever gets the chance to visit this piece of art. This specific painting shows buildings being engulfed into flames, as we can see soldiers charging to the fire. From my own depiction of this painting, it looks like most of the warriors are men, charging at the townspeople who are visibly in shock that their building has been lit on fire. It’s possible that cavalry were the front men in this operation, and this visual is the aftermath of that, but that is simply my interpretation, yours as the reading of this exhibit could be completely different. We also see the soldiers bursting through the town gate, indicating that they forced their way into the town.There is also one soldier carrying a battle flag, something I interpret to signify unity. Overall, the fire, shock of the townspeople, and the chaos of the scene all help depict the conflict of the early modern period of Japan.