Scott, Patrick, and Steffen

Introduction

Although originating far away from the archipelago in the Indian subcontinent, Buddhism became one of the biggest influences on Japanese history with a huge cultural and political impact. Due to its significance among mainly the ruling class, it has left behind a large imprint in the form of artifacts, poems, histories, and art. These remnants represent its profound impact and how the religion grew and evolved in a new environment. Numerous debates and dialogue changed how it was treated and viewed, and assimilating with pre-established Japanese beliefs made it distinct from what was practiced in other countries.

It is believed Buddhism was introduced to Japan in the 6th century (about 552 per some sources) AD by monks from the kingdom of Paekche in Korea. Many Indigenous Japanese people who worshipped the ancient Shinto religion centered around kami worship combined Buddhist doctrine with their beliefs to adjust to the new religion dominating political spheres. Buddhist, Shinto, and Confucian doctrines all fought for space in an ideologically diverse landscape and in turn left their marks on one another. Right from these early years, we can find artifacts and evidence of Buddhism in the center of Japanese history, which only grew with time. The genealogies of later artifacts from the Kamakura period and beyond can also be used to show the influence of these early developments. In the Ashikaga shogunate violence and instability saw Buddhism take a central role in many people’s personal lives. Later, in the Edo period, Buddhism’s role influencing politics diminished, although it was still a tool used to promote shogunal power, and it continued to grow with ideas coming in from China and Neoconfucian ideology. We can also see from these broader themes of Japanese history represented by Buddhist practices, such as relations with continental Asia, social stratification, and the importance of aesthetics in aristocratic culture.

The debate between the Hinayana and Mahayana strands of Buddhism was also very present from the outset of Buddhism’s arrival. Hinayana believed that the cycle of rebirth had to be repeated each time a person achieved a higher class until they reached enlightenment, in many ways elitist and self-serving of the Buddhist upper class. Mahayana believed anyone from any background could achieve enlightenment in their lifetime, but we have little evidence of Buddhism being represented among the lower classes and common folk in Japan. Many of the artifacts were created for the upper classes, which still provided a strong consumer base for Buddhist goods and art.

One Mahayana strand, Zen Buddhism, became very popular. It originated in China and focused on seated meditation (zazen) as the path to enlightenment. It focused on simplicity and embracing the natural world and inspired various art and court aesthetics. Foundational to Buddhist practices in the Heian period were esoteric rituals from China, popularized by Kukai and his Shingon school. Mantras, mudras, and mandalas embodied these secretive rituals and were highly valued by elites. Their style can be seen in lots of art from that period. Pure Land Buddhism, another Mahayana sect, rivaled the popularity of Zen Buddhism. It focused on the figure of the Buddha Amida as a savior, preaching that accepting the savior was the path to enlightenment rather than secretive, complex rituals and internal mindfulness. Its emphasis on vivid imagery also produced some of the best art from premodern Japan.

Our artifacts stretch across centuries and display all these historical narratives, although there are plenty more we could not cover in six examples. They range from simple clay structures to elaborate paintings and display the evolution and changes in Buddhism. The dynamic nature of Buddhism can be used as a lens to track the pulse of Japanese society throughout its history, both with broad political implications and to understand the inner workings of the lives of individuals, and together our images paint a broad picture of the imprint religion creates on cultural history.

Early Japan and Heian Period

Lineage Portrait of Buddhist Monks

The Lineage Portrait of Buddhist Monks features twenty-four Buddhist monks arrayed in 5 rows with one alone at the top. The monks are likely members of the same school but over several generations, and the man at the top is possibly the founder of the school. These schools of esoteric and Zen Buddhism involved an expert teacher directly passing schools unique knowledge and practices down to individual students. Jstor suggests the portrait may be representing monks from the Ōbaku school, a form of Zen Buddhism founded in Japan by Chinese emigrant monks. It was likely influenced by the Shingon school, founded by the legendary monk Kukai, which introduced Chinese-style esoteric rituals to Japan for the first time in the 9th century. Having a smaller number of monks in the painting could represent how Buddhist teachings were esoteric, which means that Buddhist teachings were intended for only an elite small group of people. Esoteric Buddhism also contained a lot of rituals and recitations, focusing a lot on mandalas, mudras, and mantras. They were highly secretive and privatized, and being one of the monks in these schools was a high social honor as the depiction in this image glorifies the wisdom and rare knowledge of these monks.

(Written by Scott Sweeney)

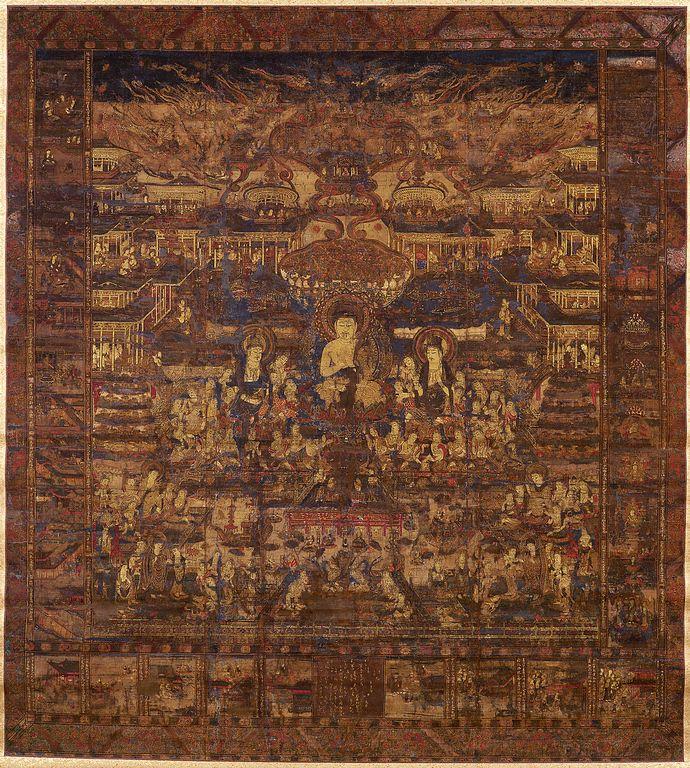

Taima Mandala

The Taima Mandala represents Amida Buddha and his Western Paradise, also called the pure land. People who are believers in the Buddhist religion are reborn in the pure land to attain their quest for Nirvana. Nirvana is a transcended state where believers are free from suffering and desire. In the state of Nirvana, they are free from karma, and the samsara cycle Nirvana represents the final goal of Buddhism. As depicted in the Taima Mandala, the deceased are reborn on lotus pedals. The lotus is the central symbol of Buddhism; it represents enlightenment and purity; the lotus also grows out of muddy water. However, it remains clean, connecting this with Buddhism, as the murky water depicts the suffering of the reborn followers. Where Amida Buddha sits, many deities and devout followers surround him. His grand palaces surround him, and the background is filled with musicians and deities. The Taima Mandala is an incredibly detailed depiction of Buddha and the pure land surrounding him. Buddha is depicted as a caring and generous figure through his facial and physical expressions, with his hands crossed laying on his chest. Surrounding Buddha are other divine figures who are welcoming people on their journey towards enlightenment. The image also incorporates incredibly detailed Japanese architecture that is constructed symmetrically throughout the image. These grand structures and temples help to frame the importance of Buddha’s surroundings as perfect. The first Taima Mandala was painted in the 8th century, and many copies, such as this one, were made as Buddhism gained popularity in the 12th This image was significant in its depiction of religious iconography, which was a form of religious practices that was previously unknown. This religious practice was new to the time and helped Buddhism grow, as they combined Japanese art, culture and religion with each other.

(Written by Scott Sweeney/Patrick McGeoghean)

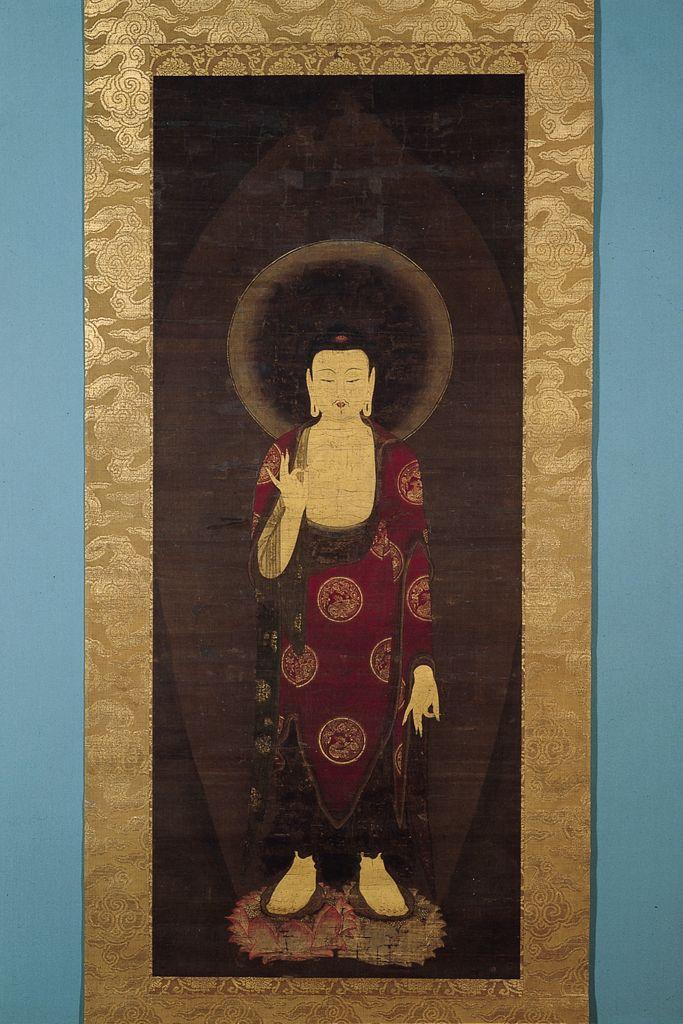

Descent of Buddha Amitabha

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14992796

This is a hanging scroll estimated to be from the 13th Century, during the period of the Kamakura Shogunate. It depicts the Buddha Amitabha, who is a hugely influential figure in Pure Land Buddhism throughout Asia, and in Japan is generally referred to as Amida or Amida Raigo. Worship of the Amida started to appear in Japan in the mid-Heian period(although it had started much earlier in China) and would grow in popularity throughout the end of the Heian period and continue into the Kamakura period. The Amida is identified in the works by the symbol he is making with his hands, an example of a Buddhist mudra. He is depicted dressed in very simple robes, but with a halo behind him to represent his holiness and enlightenment.

Amida was given a god-like status and monks preached that a shortcut to enlightenment was to pronounce him as the savior by chanting “Namu Amida Butsu” (roughly “I take refuge in Amida Buddha”) in the streets. The monk Honen(1133-1212) is generally credited with the rise of Pure Land Buddhism in Japan. He promoted the praise of Amida as the best method for enlightenment in contrast with other rising popular Mahayana practices like Zen Buddhism and the beliefs of the Lotus Sutra. It was this specific vision of Amida as a savior figure that differentiated Pure Land Buddhism from forms that emphasized enlightenment through secret complex rituals, monastic lifestyle and meditation practices.

(Written by Steffen Oosten)

Kneeling Woman

The Kneeling Woman is a clay sculpture from the Nara period, estimated to be early 8th century. It is emblematic of many Chinese sculptures from the 7th and 8th century. The hair style, parted in the center and with a bun at the back, and clothing, a full-length gown tied by a long sash, were both common among women in Tang China. What she is doing is unclear, perhaps in prayer or meditation. It has also been suggested she is a mourner at the death of a Shakyamuni, or a witness to a famous Buddhist debate between Vimalakirti and Manjushri, both events detailed in sutras.

This figurine was likely one of a much larger group located in Nara, where the first permanent capital was established by Empress Genmei. It was likely one of the earliest Buddhist temples in all of Japan. The similarities it has to Chinese models represents how strongly early Japanese Buddhism was based on influences coming from the continent. During this time, the Japanese Emperors sent waves of delegates to the court of the Chinese Tang dynasty to gather knowledge on a variety of topics and combine what they reported with Japanese tradition to inform their vision of how Japan should operate. Prince Shotoku’s Constitution also solidified it as the religion of Japanese bureaucracy. The emperor and aristocratic classes adopted it early on, but Buddhism remained highly political and elitist and never diluted down to many common people. Evidence like these sculptures are found in places like capitals, where elites may have lived, but there is little evidence of widespread buddhist worship among the broader populace, and it is likely they continued Shinto worship. The temple was likely located in Nara because its status as a permanent capital meant proximity to the Imperial court, where aristocrats would have high demand for Buddhist practices. These upper classes also aspired to associate themselves with Chinese styles such as those shown by the figurine.

(Written by Steffen Oosten)

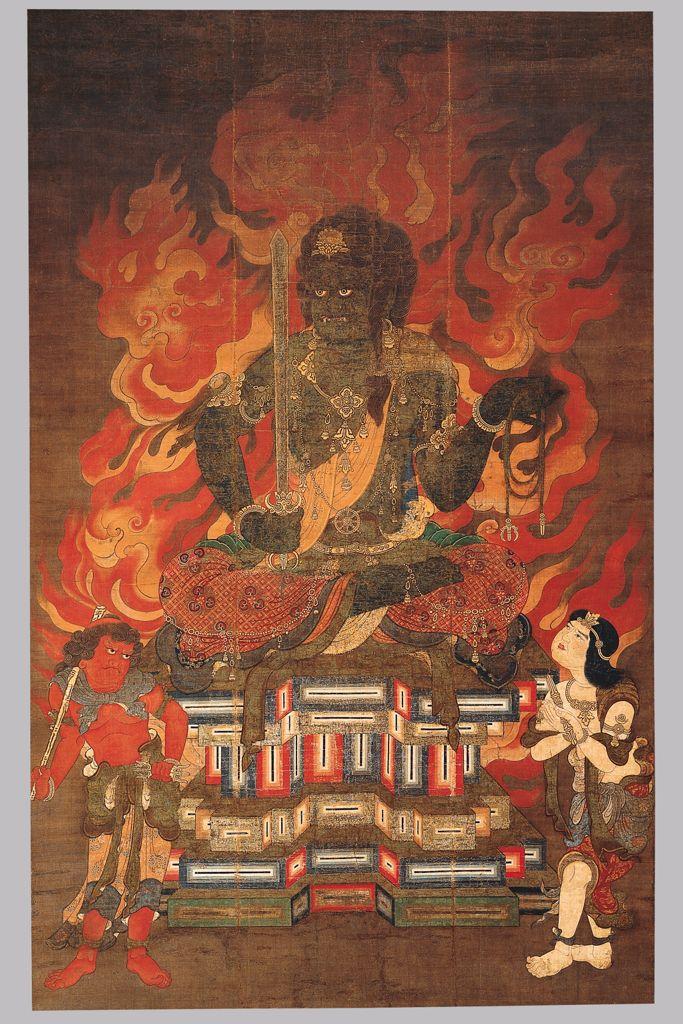

Achala Vidyaraja (Fudo Myo-o) with Two Attendants

The Achala Vidyaraja (Fudo Myo-o) with Two Attendants depicts Achala, one of the wisdom kings. According to the jstor description, Achala’s name means ‘immovable’ and is depicted in the image as a domineering, almost frightening figure. This depiction of the religious deity Achala serves to express his importance in Buddhism by evoking a sense of emotion from whoever studies the image. Achala is painted green, sits with his legs crossed and has almost animalistic teeth. He is covered in ornate jewelry and clothing patterns across his body, while he holds a sword in one hand and a lasso in the other, items that are not associated with peace. He is surrounded by imagery of flames and fire behind him, which continues to build up the expression that he is a dominant figure. Beneath Achala, two beings are depicted that seem to be his servants. The figure on the left seems to be male, while the figure on the right seems to be female, however, according to the jstor description they are both two of his ten male attendants. What seems to be different about this image in comparison to others are the bright colors that the artist used to depict Achala. Also, I find it incredibly interesting that he is depicted as a figure who evokes a sense of fear, which seems unique to other depictions of Buddhist figures.

(Written by Patrick McGeoghean)

Kamakura and Ashikaga Shogunates

Six of the Twelve Divine Generals (Jūni shinshō)

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/75292

These are a set of six small wooden figurines dated to the early 1300s during the last decades of the Kamakura period. They are possibly what remains of a larger set, as they are representations of six of 12 Divine Generals. According to the Sutras, the 12 Divine Generals are responsible for defeating enemies of Buddhism, fighting intangible foes such as sickness and mental ailments preventing internal peace and enlightenment. They have painted faces, fighting countenances and generally a fierce, angry look.

They are also shown wearing armor which is elaborately designed and painted even on the small surface of the figures and looks to resemble early samurai armor of the time. This represents how the militarization and consistent violence of the Kamakura period influenced the culture of Japan as a whole. Samurai and warrior values were already viewed as something to be admired, and as a result in the following Ashikaga and Tokugawa shogunate’s Samurai lifestyles were imitated and copied by people of all classes and origins, including in religion. While the violence and military prevalence seems counterintuitive with the peaceful nature of Buddhism, many began to turn to it during times of instability and danger for inner solace. This contributed to the rise of Zen Buddhism during the Kamamkura shogunate, which involved lots of meditation, stillness, and mental calmness. The figures would help with this specific practice, as they were intended to ward off nonphysical dangers that would affect mindful meditation. It is also possible that they were used as a preventative mechanism against undiagnosed mental illness caused by the brutal fighting apparent during the period.

(Written by Steffen Oosten)

Buddha Vairochana in the Form of Ekaksara-ushnisha-chakra

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14994679

This is a silk hanging scroll from the 14th century, believed to have been created in the first few decades of the Ashikaga Shogunate, depicting the deity Vairochana. Vairochana, whose name means “infinite light,” is worshipped as the primary Buddha in the Shingon sect of Esoteric Buddhism. The painting depicts Vairochana as the Buddha of the Golden Wheel. The Buddha has an oval face with long, narrow eyes, a full nose, and pursed lips. The figure has narrow shoulders and a small torso. Scarves are found hanging off of him, and he wears a crown and a sash which ties his lower garments. Vairochana is seated on lotus petals in meditation and is holding his hands in a gesture known as the wisdom fist. The wisdom fist is a gesture where the index finger of the left hand is extended into the right fist, symbolizing the unity of sacred wisdom and human ignorance. The stylized flames surrounding his head represent mystical emanations, while the tiny buddhas in his headdress indicate his wisdom.

This is a perfect example of the esoteric buddhism that was widely popular with Japanese elites. The hand movements are some of the highly valued mudras, both within and beyond the Shingon sect. These are possibly teachings passed down directly from the schools founded by Kukai, who got his education in Tang China. Images of Vairchana appeared to have been very common in Japan in the Kamakura age, and he was likely one of the leading Buddhist deities. Images of him are also found quite prevalently in the Heian period.

(Written by Scott Sweeney)

Hossō Mandala

Created during the 16th century, The Hossō Mandala depicts Buddha surrounded by many enlightened figures below him. These enlightened figures are arranged in seemingly hierarchical positions above and below one another, with the highest representing the most spiritual. What is interesting to me is that all of the figures are bald and dressed the same exact way, besides one. One of the enlightened figures has facial hair and hair tied back. Some of the figures are holding their own hands, in a form of prayer or meditation, while others are holding sacred objects. These objects range from ornamental staffs and plates to sacred texts and scrolls. Buddha’s left foot is also positioned on a lotus flower, representing his purity and spiritual power. None of the other enlightened beings are touching a lotus flower, framing him as more divine than the rest. A tag is placed next to each figure, which presumably holds their name or title. The Hossō Mandala serves to depict Buddha as an enlightened being who is on a different plane than the rest of the spiritual figures in the painting.

- (Written by Patrick McGeoghean)

Edo Period

Bronze Crucifix with Buddha

This crucifix was created during the Edo period; it is made of bronze. Right in the center of the cross sits a Buddhist monk. This Buddhist monk is most likely to be an example of the Amida Nyorai Buddha who is cross-legged and praying. This work is from a group of hidden Christians in Japan known as the “Kakure Kirishitans.” Portuguese Catholic missionaries influenced the Kirishitans, when the missionaries arrived in Japan in 1549. The Portuguese spread their faith to the Japanese until 1614, when the Tokugawa Shogunate Ieyasu banned Christianity, seeing it as a threat to their empire. Eventually, Japan isolated itself in 1647 as its rulers shut off trade and contact with the outside world. Japanese Christians had to find ways to continue worship underground, which they continued to do throughout Japan’s history. This cross exemplifies how the hidden Christians combined symbolism from Buddhism and Christianity for worship. When the religion was first practiced, the Kirishitans would often draw a cross on a piece of paper to remind them of their beliefs in visual form. The evolution of the crucifix shows the evolution of how the Kirishitans practiced Christianity even though they were forced to keep it a secret.

(Written by Scott Sweeney)

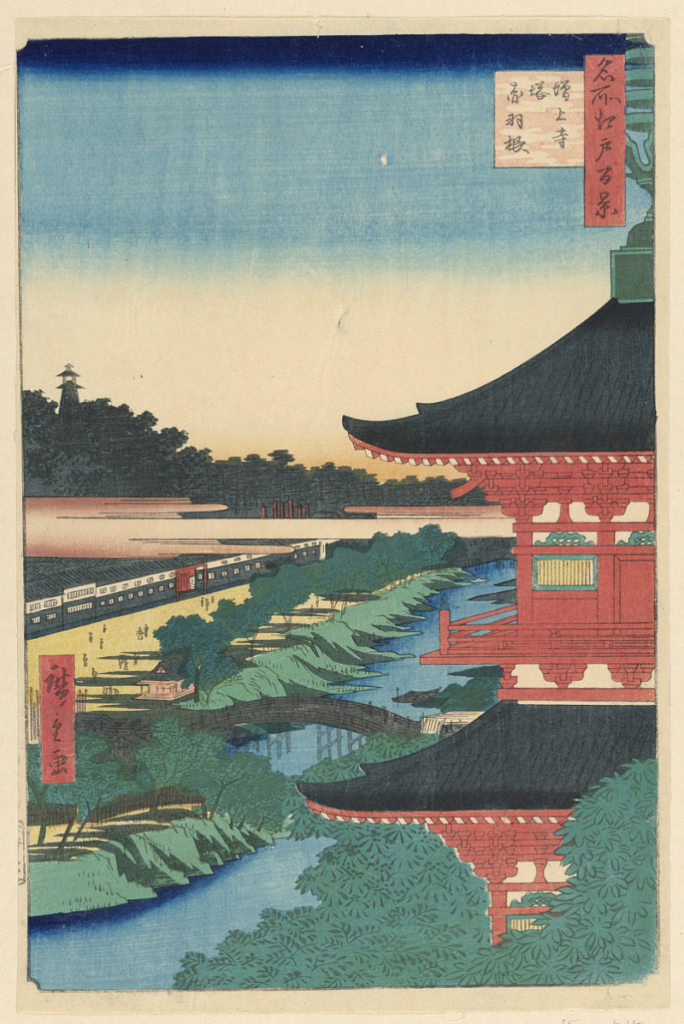

Pagoda of Zojoji Temple, Akabane (Zojoji-to, Akabane) From the Series One hundred Views of Edo

This is an illustration of the Zojoji Temple, constructed by Tokugawa Ieyasu at the start of the Tokugawa Shogunate. The temple, which still stands in modern Tokyo today, was built just outside Edo where Ieyasu settled his capital. It likely served as the seat of cultural power away from Kyoto, where the Emperor’s palace was the nation’s center of religion. The temple was a massive 5 story pagoda constructed outside the city’s boundaries at the time to be more secluded, closer to nature, and overall ascetic, while still in proximity to the capital elites. It was also important to build an important temple near the seat of power for the Tokugawa’s strategy of using buddhism to justify their rule. By doing things such as commissioning the building and illustration they legitimized the claim that were aligned with Buddhist philosophy, protecting worshippers’ religious beliefs, and possibly had divine support. This also helped them appear aligned with the Emperor’s will as his servant, as the Emperor was a highly religious figure and it would be his wish to spread spirituality and worship.

The temple served as the regional center for worship of Pure Land Buddhism. The Pure Land sect had been prevalent in Japan for several centuries and been embraced by elites since as far back as the Kamakura shogunate. This can be seen by other elements of our exhibition such as the Taime Mandala and Descent of Buddha Amitabha. Pure Land Buddhism and other sects, notably Zen Buddhism became increasingly competitive with one another in the Tokugawa shogunate, more than in earlier times. However they did not wield as much influence on the government as before, as Shoguns instead used internal conflicts to their own advantage.

In the background of the illustration you can also see a watchtower, which although likely not the artist’s intention, symbolizes how the Tokugawa regime used various tactics to consolidate power. The shoguns used Buddhism as a tool to appeal to the masses and legitimize their regime, but also used military might to keep an enforced peace and were constantly on the lookout for any threat to their regime.

(Written by Steffen Oosten)

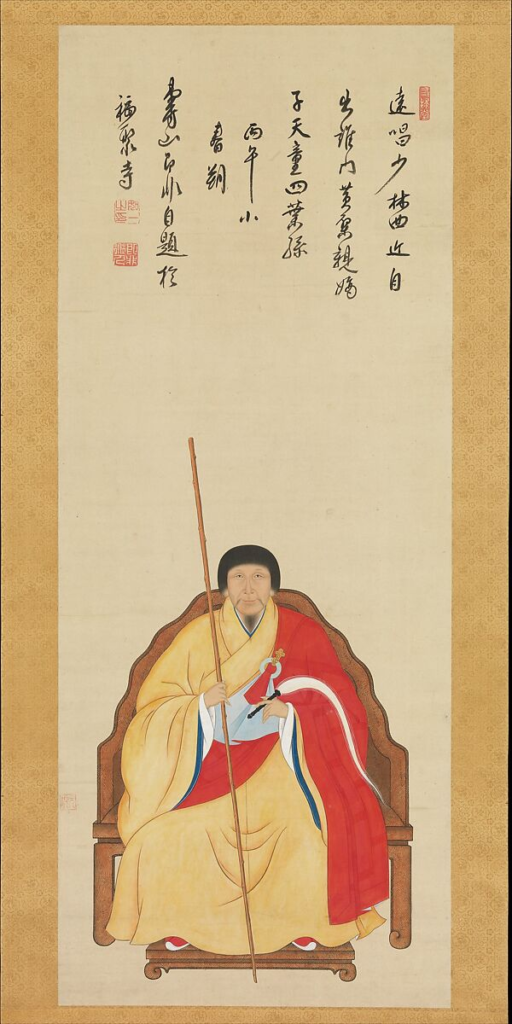

Portrait of the Ōbaku Zen Monk Jifei Ruyi (Sokuhi Nyoitsu)

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45378

This is a portrait as part of a hanging scroll, believed to be from around 1666. It depicts Jifei Riyu, a master in the Obaku sect of Buddhism and a Chinese Immigrant who popularized the Obaku school in Japan. Jifei is seated in traditional robes holding a staff in his right hand and what I believe is some sort of brush in the other, likely used for a ritual of some sort, given that Obaku utilizes esoteric teachings. However mudras, mandalas and mantras were less common than in Pure Land Buddhism. Less imagery is also traditionally used in Zen Buddhism, explaining why the scroll is so simple as opposed to some of the more intricate drawings and objects seen elsewhere in this exhibit. The calm facial expression is likely also emblematic of the ascetic, meditative lifestyle of Zen monks. The inscription above tells the story of Jifei, as a sort of biography and list of his accomplishments. Hanging scrolls became very prominent in Japan over the course of the transition from the medieval to early modern age, merging religion, messaging, teaching and biography. Having a scroll of the one’s teacher or the founder of a sect was highly important within Buddhist religions, especially since the relationship directly from pupil to teacher was emphasized as the main passage for learning.

Although at this point the Tokugawa regime had largely closed itself to immigration, interaction with trading partners continued and some were still allowed to move to the archipelago in the early times of the shogunate. Jifei was one of several monks allowed to enter the country through the port of Nagasaki, who spread not just Buddhist ideals but also new Confucian ideology. The writing in the scroll is in Chinese, symbolizing the impact Chinese migrants had on Japanese worship. Chinese Schools were also settled throughout the country to teach youths Neoconfucian ideals and Chinese perspectives on things like manners, literature, art, and history. This was embraced by the regime as the Chinese ideology could be used to support their claim to power, diversified education, and continued a long tradition of borrowing elements of Chinese culture for Japanese use.

(Written by Patrick McGeoghean)