Introduction:

The Kamakura period is a time that saw the influence of Buddhism throughout Japanese society. During this time art was used as a way to express the strength and power that Buddhism was starting to hold in Japan. An example of this is in the Sculpture of Aizen Myoo the Buddhist deity. The figure looks powerful and menacing but the reason for this is to protect itself and its Buddhist followers. Aizen Myoo is a deity that is a symbol of protection against evil not harboring it. It signifies the concept of fighting fire with fire. The deity acts and looks scary so real evil things don’t come near it. The Deity has six arms that used to hold a thunderbolt, an arrow, bell, bow, lotus flower, and clenched fist. These things mostly being weapons and things that can be used for destruction, but instead this deity uses them as protection and its message is spread to bring its followers to peace. This statue symbolizes Buddhism’s belief in peace and prosperity, but brings in the element of the need to be strong and protect yourself. Which as a notion ties to the Kamakura period itself, because this was the start of more military emergence in Japanese society.

This period transitioned from courtly rituals to military power. Japan was looked at as a prized country and so they prioritized themself in having a strong military. The Mongols invaded in 1274 and then again seven years later but the rise of power through the military helped defend Japan and also defend religious practices. It also sparked a rise in the Samurai class spiritually.

Japan’s military power and religion reflect a relationship between the samurai class, shogunate, and other religious practices. Religious support for the shogunate was shown from the Hojo regents who were heavy supporters of Buddhism. The Hojo regents promoted the construction of temples and helped spread the word of Buddhism. Religious figures and people in power supported the Shogunate. The alliance between them helped maintain social order and stability during the Kamakura period. The Shinto belief played a crucial role in justifying military actions. For example, Samurai and Shogunate leaders sought blessings from Shinto deities before engaging in battle. This was because of the belief that divine favor would ensure a victory. There is also interplay between religious institutions and political power. This is portrayed with Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines. This is because they owned lots of land, collecting taxes, while also maintaining private armies to protect their interests. People like warrior monks or, sohei, had considerable military power. These monks often intervened in conflicts with other temples or secular authorities. This demonstrates the crossover between religion, power, and military in the Kamakura period.

Graham Roberts

- Fiery War Image

The “Night Attack on the Sanjô Palace” is an intense depiction of a key event in Japan’s medieval history. Created in the second half of the 13th century during the Kamakura period, this handscroll (45.9 x 774.5 cm) tells the story of the Heiji Rebellion (1159-1160), a violent power struggle that shaped the era.

The scene captures the chaos of a nighttime assault on the Sanjô Palace. Flames engulf the wooden structure, filling the background with vivid orange and red swirls of engulfing smoke, while warriors on horseback and on foot storm through the scene in a haze below. The scroll is full of movement, with charging horses, swinging weapons, and panicked figures fleeing the fire. Every detail, from the warriors’ armor to the palace architecture, feels deliberate, pulling you into the action even all these years later. The splatter of red throughout makes you think blood is everywhere, and this is a very brutal attack. The composition leads the eye along the scroll, creating a sense of depth and urgency as the story unfolds.

What stands out is how the artist portrays the destructive force of war. The fire symbolizes not just physical destruction but also the collapse of order during the late Heian period. The chaos under the smoke is intentional. The carefully drawn details of the samurai reflect the growing importance of warrior culture at the time. This scroll doesn’t just record history—it feels like an emotional retelling, balancing the brutality of battle with the artistry of its depiction. It feels like there’s impending doom with the It’s amazing how much of the tension and drama of that moment is still alive in this centuries-old artwork.

2.Two men in a garden

This photograph captures a poignant moment of cultural transmission, as an older Japanese man instructs a younger man in the traditions of Zen gardening. Their dark, shadowed figures are crouched around carefully arranged rocks on the floor of what appears to be a monastery, set before a meticulously raked Zen garden made of sand and stone. The serene garden, framed by a lush forest, provides a contemplative backdrop that underscores the scene’s timeless quality.

The image dates to the Heian period, suggested by the men’s traditional Japanese garments, a hallmark of the era’s cultural values. During this period, Japan was undergoing rapid modernization fueled by the post-war economic boom. Despite this, many individuals sought solace in age-old practices like Buddhism, which emphasized simplicity, harmony, and introspection.

The interaction between the two men illustrates the deeply rooted hierarchical structure of Japanese society at the time. The younger man’s attentive demeanor reflects the cultural norm of profound respect for elders, who were seen as bearers of wisdom and tradition. It represents values of the culture.

Zen gardening itself embodies these principles, as its design requires patience, discipline, and an understanding of nature’s balance. The older man’s role as teacher symbolizes the preservation of cultural heritage in the face of rapid societal change, a theme that resonated strongly in the Heian Period.

Through its interplay of light, shadow, and human connection, this photograph encapsulates a moment where tradition and modernity meet, serving as a testament to the enduring importance of cultural continuity.

3. Women in Heian Period

This image portrays a scene from Japan’s Heian period, a time renowned for its refined court culture and artistic achievements as well as power dynamic between men and women. The figures, likely noblewomen, are depicted in a domestic or ceremonial setting, dressed in jūnhitoe, the multi-layered kimono representing high social status.

Women in the Heian period played significant roles in Japan’s courtly and cultural life even though living in a patriarchal society. They were treated better and many monumental movements/ events were because of women.

Their long, flowing black hair reflects Heian beauty standards, while their postures, one seated formally and the other one is kneeling, convey much respect. This was expected out of women by the men. Power was granted to the men but women were still very well educated for the most part.

The setting, characterized with elegant with open spaces, sliding screens, and floral motifs, underscores the era’s aesthetic sensibilities. This scene captures the Heian elite’s focus on elegance, ritual, and the pursuit of cultural sophistication.

4. Significance of Religion in Early Modern Period

This image represents religion which played a huge role in maintaining the Tokugawa regime. The shogunate utilized Shinto and Buddhist practices to reinforce its authority during this period along with having a strong military. It can be understood that power and religion were intertwined in Tokugawa Japan.

Power was expressed not only through governance and military might but also through the careful orchestration of rituals and ceremonies that aligned with religious and philosophical ideals, ensuring the continued stability and legitimacy of the ruling order.

In the picture, it shows people sitting in specific places. Power and authority were huge components to religious practices. Religious practices helped the people stay in check with the norms that everyone was held too. It was believed that if the people were held to a standard of devoting their life to their religion (Shinto or Buddhism), it would prevent rebellions and a downfall of society. Respect for the higher ups created stability within society.

Shown in the picture, we can see how formal this practice is. This was the standard for all practices. Having a formal/ well presented religious practice meant that stability and loyalty were current.

Elliott Hamblett:

Bodhisattva Kshitigarbha (Jizo Bosatsu)

The start of Buddhist Influence in Japan

Pictured above is the statue of Ksitigarbha a revered Bodhisattva sculpted in the Kamakura period between 1223 and 1226. The sculpture is made of cypress wood embellished with cut gold leaf. . Kshitigarbha is depicted as a Buddhist monk with a shaved head, robes, and a staff. This sculpture was made to signify his role as a guide and mentor for people, helping them by granting their wishes. He was seen as a protector in Japan for the deceased, women, and children.The arrival of Buddhism in Japan in the Sixth century, mostly from Korea. Had a strong impact on the country’s religious, cultural, and artificial landscape. Buddhism gained traction and influence in Japan through political and social struggles. By the Kamakura period when the sculpture was created, Buddhism had significantly expanded across the country. Many Buddhist figures during this time were more centered around the esoteric teachings of Japan’s elite. Kshitigarbha was different from these figures and was more accessible and compassionate to the common people of Japan. The sculpture is standing at the Asia Society Museum in New York. Kshitigarbha appears as a leading symbol for the spread of Buddhism in Japan during this time. The sculpture itself also leaves a legacy of Buddhist strength and influence in Japan.

Ancestor Rites: Ritual for feeding the hungry ghosts in Japan using wooden hands at Mampuku Temple on Mt. Obaku.

A Buddhist Ritual that still stands today

The photo above takes place at the Mampuku Temple on Mount Obaku, Japan. The Buddhist ritual; Hungry Ghosts takes place here. This ritual is embedded in the belief that the deceased still have souls even after death. The reason for the ritual is to help these deceased souls find peace and nourishment as they could be feeling neglected. At the Mampaku temple the wooden hands shown are used as a symbolic holder to receive offerings. The ritual also involves the community bringing food and prayers to the temple to show their appreciation for the deceased spiritually letting them know that they are not forgotten. This spiritual ritual shows the connection in Japanese Buddhist practice between the living and the dead. The use of the wooden hands is to visually demonstrate the seriousness of the Japanese Buddhists’ connection to the material world and the deceased. But not any deceased people this ritual is focused on the honor of their ancestors. It shows the powerful bonds that these Japanese families have with their ancestors and they want to still connect with them even after death. Something unique to Japanese Buddhism and almost unheard of in many parts of the Western world.

Aizen Myoo (Ragaraja)

A Buddhist symbol of strength and Power

The sculpture above depicts a deity in Japanese Buddhism, mostly in Shingon and Tendai traditions. Shown in a fierce, powerful, and even frightening way, the deity is actually a symbol and protector against evil. His appearance is the way it is to scare away evil and immoral things from coming close to him and Buddhists. The sculpture was crafted during the Kamakura period, crafted from wood and painted with black lacquer. The dark black color tone adds to the theme of darkness and imposing fear on evil. The deity has six arms which used to hold six attributes to reaffirm power: a thunderbolt, bell, bow, arrow, lotus flower, and a clenched fist. These objects represent the deity’s ability to combat evil desires and lead its followers towards a path of peace. The third eye on the deity’s forehead shows his insight into the world around him. The meaning behind the deity and the statue is to be a protector for those around it and Japanese Buddhists. The statue stands in the Cleveland Museum of Art and is a significant example of religious art during the Kamakura period. It acts as a symbol of protection and power which shows the significance of Aizen Myoo’s presence in Buddhism.

APAN. 2000. Shinto, the way of the Kamis (deities) is the original religion of the Japanese

How Buddhist and Shinto religions still stand strong have strong presences in Japan today

The photograph taken in 2000 shows the bride in traditional Kimonos following a Shinto wedding ceremony. Shinto means “the way of the Kami (spirits)”. Shinto is Japan’s indigenous religion rooted in the belief that Kami live in the natural world; for example in rivers, people, animals and even in the dead. The Kami bring good things like life and prosperity to its followers. Shinto is largely influenced by Buddhism and the belief of a mythical creation of Japan from the Kami. This photo demonstrates the power of these Shinto traditions still in today’s society. During World War Two when Japan was under Imperial rule, the Imperial government tried to undermine people from expressing homage to Buddhism and Shinto religions. There was an effort to suppress Japanese people from showing and practicing their cultural heritage. But the power Shinto and Buddhism had in Japan was too strong and continues to this day. The outfits pay tribute to their ancestors, the Kami from the Shinto religion, and the influence of the strong lasting effect of Buddishm in Japan. It shows that people in Japan today are still very connected to their cultural heritage and honor it still in important ceremonies like weddings.

Robbie Thomas

Funeral of Genji – Jomon Period:

Image URL:https://www.britannica.com/media/1/301018/242096

This painting is a depiction of Genji’s funeral, in the painting portrays a scene with sorrow following the passing of Hikaru Genji. The central figure in The Tale of Genji novel series, by Murasaki Shikibu. In this artwork individuals come together around a funeral structure with flowers and tributes creating a tranquil ambiance. The sorrow depicted on the characters’ faces conveys a sense of sadness and emotion. Evident in Murasaki’s demeanor as Genji’s grieving widow in the painting, from the Heian era that beautifully captures the intricate details and elegant attire reflective of that historical periods cultural significance. The environment of the funeral shows a scenery that contributes to the atmosphere of sorrow at the funeral. The placement of each character is carefully done to highlight their relationships, with Genji and among themselves. Murasaki, Genji’s widow, is especially heartbroken, highlighting the personal impact of his loss. She is seen right in front of the shrine mourning her husbands’ loss. This artwork allows viewers to admire not the aesthetics of the period but also the profound emotions depicted in Genjis story. The painting is a tribute, to a character whose existence deeply influenced those, in his circle and left behind a legacy of love and sadness that lingers on. It captures the moment of bidding farewell to Hikaru Genji beautifully while showcasing the emotional tapestry of The Tale of Genji.

Dogu Figurine – Jomon Period:

The dogū figurines serve as profound representations of the intertwining of religion and power during the Jōmon period (circa 14,000 to 300 BCE) in Japan. Often characterized by their exaggerated female features, these clay figures are predominantly believed to symbolize fertility and the earth goddess, reflecting the spirituality deeply embedded in Jōmon society. The veneration of fertility and maternal figures suggests that the Jōmon people likely relied on these deities for agricultural prosperity and safe childbirth, underscoring the vital role of women in communal power dynamics. The societal structure of the Jōmon period was complex; while generally perceived as egalitarian, emerging evidence indicates that some individuals held specific religious roles, possibly connected to shamanistic practices. The presence of dogū as ceremonial objects hints at the necessity of ritualistic engagements in everyday life, potentially granting spiritual leaders elevated status within their communities. In this way, dogū not only reflect a religious aspect of daily existence but also signify the power dynamics that shaped social hierarchies. Ultimately, these figures embody the profound connection between spirituality and authority, revealing how the Jōmon people navigated their environment through belief and reverence for the forces of nature.

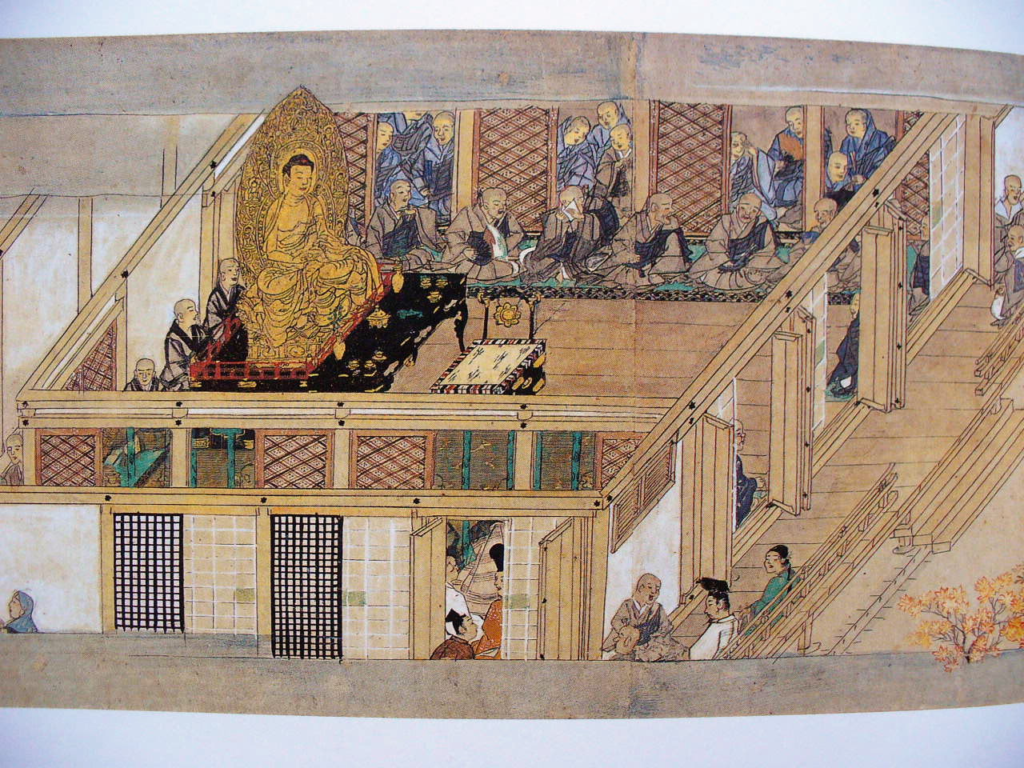

Hōnen Shōnin Eden – Ohana Debate – Medieval Period:

Image URL: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Honen_shonin_eden_-_Ohana_debate_01.JPG

Ohana Debate” is evidence of how religion and political power have interplayed in every inch of Japan’s medieval time. The painting captures an intense period of dialogue and disputations between religious leaders and those wielding political power, capturing a scene of how belief became a vital part of political exercise. In light of the society ruled by samurai, religious powers took more influence because the ruler legitimized themselves with authoritative Buddhist institutions. In the “Ohana Debate,” the central figures are representing of opposing views and reflect the struggle for power between warrior elites and monastic authorities. This therefore highlights Buddhist teachings as not just personal beliefs but significant constituents of social and political discourses. The debate represented in the painting is representative of the ongoing negotiation that is taking place between spiritual idealism and the pragmatic practice of governance. Moreover, participation by different leaders in the debate signifies the social expectation from political authorities to validate their rule based on the moral and ethical frameworks offered by religion. Therefore, “Ohana Debate” is a significant artifact of history that reveals the interaction between spiritual conviction and political ambition in shaping not only the identity but also the governance of medieval Japan; it is exemplary in bringing out the role of Buddhism in the legitimation of temporal power.

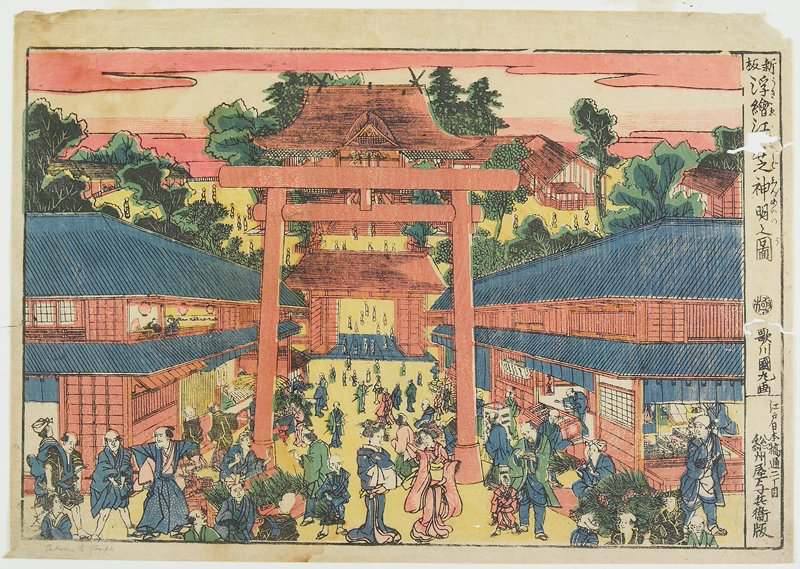

Shinto Shrine – Tokugawa Period:

Image URL:https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45095

The Shinto shrines gained momentum during the Tokugawa period,from 1603 to 1868, as dynamic symbols of religious and political authority within Japan. It was during this period that a centralized government was formed under the Tokugawa shogunate, which wishedto establish its legitimacy through links with the indigenous Shinto faith. Shinto shrines were not only places of worship but also played animportant role in the social and political life of Tokugawa society. Consequently, the proliferation of local shrines throughout villages became a way of fostering community identity in every region because its shrine was often dedicated to a mythic founder, reinforcing local government tied to the shogunate’s directives. Additionally, shrines of importance, such as the Ise Grand Shrine, had nationwide symbolic meanings and attracted mammoth pilgrimages that made claims by the shogunate over divine legitimacy and national unification even more effective. The elite class, including the samurai, patronized these shrines in order to prop their status and frequently engaged themselves in rituals interconnecting religious observance with claims of power. Shinto shrines in the Tokugawa period best personified the interaction ofreligion and governance and gave sufficient proof of how ingrainedspiritual beliefs shaped political authority and social hierarchy in Japan.