Conor O’Hara, Kaz Osawa, Drew O’Connell

Introduction

This exhibition focuses on historical images of Japanese masculinity in peace and war. Gender has featured prominently throughout Japanese cultural history and is often expressed through various different forms of art. Artistic mediums like sculptures, paintings, and wood prints have been used to highlight the intersection between gender and other aspects of Japanese cultural history like war, politics, and social changes. The pieces of art that will be shown in this exhibit aim to highlight the continuous shifts in conceptions of masculinity across time.

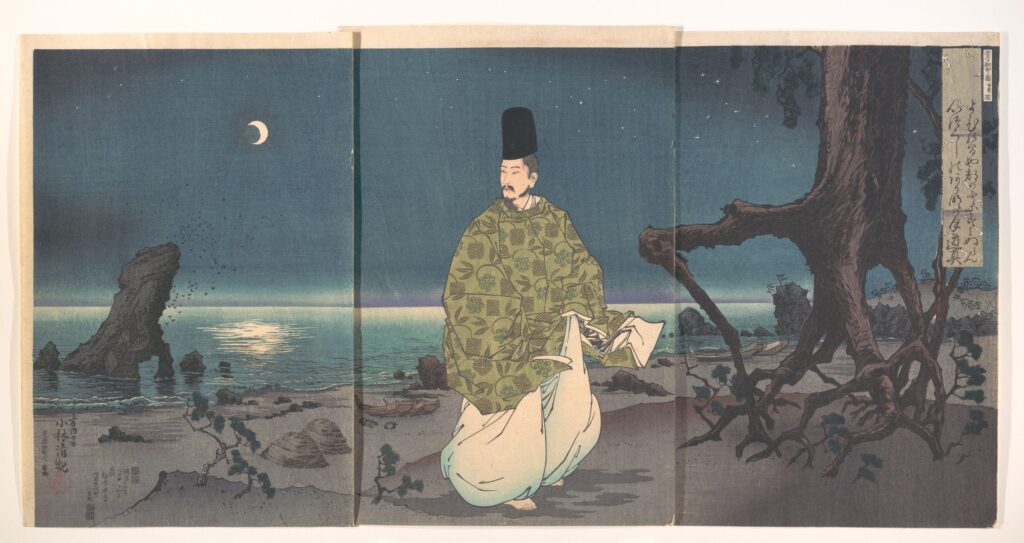

During the Heian period, masculinity was deeply tied to aristocratic culture, particularly the harmonious connection between man and nature. This connection was expressed through cultural refinement, where men were celebrated for their poetic skill, aesthetic sensibilities, and romantic pursuits. Masculinity during this time was not primarily defined by physical strength, but by intellectual interests and one’s connection to nature, which were seen as markers of status within the imperial court. Artists often used metaphors drawn from nature to convey these ideals, emphasizing the beauty of the natural world and its connection to human emotions. A notable example of this is the image of the “Moonlight Courtier,” which includes detailed depictions of nature to symbolize the interplay between masculinity and the courtly qualities admired in Heian period masculinity. This image reflects the broader cultural values of the period, where a man’s ability to engage with and reflect on the natural world was a key component of his identity.

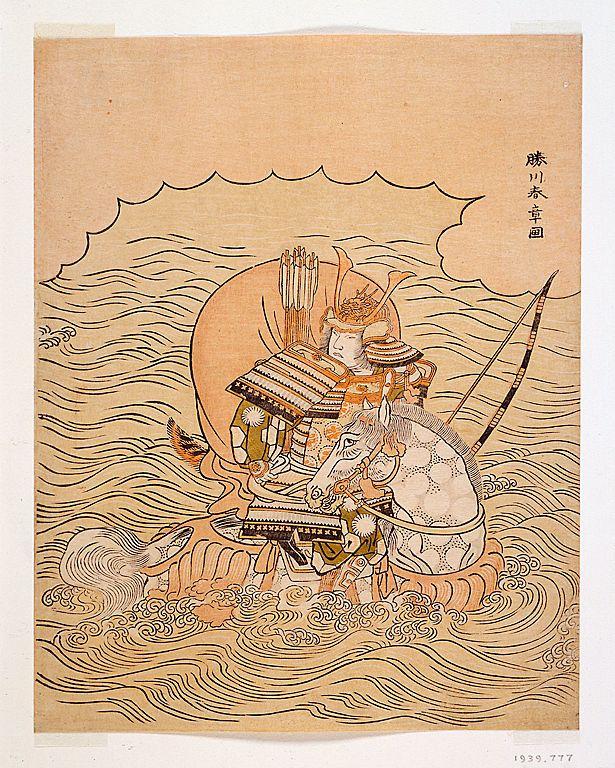

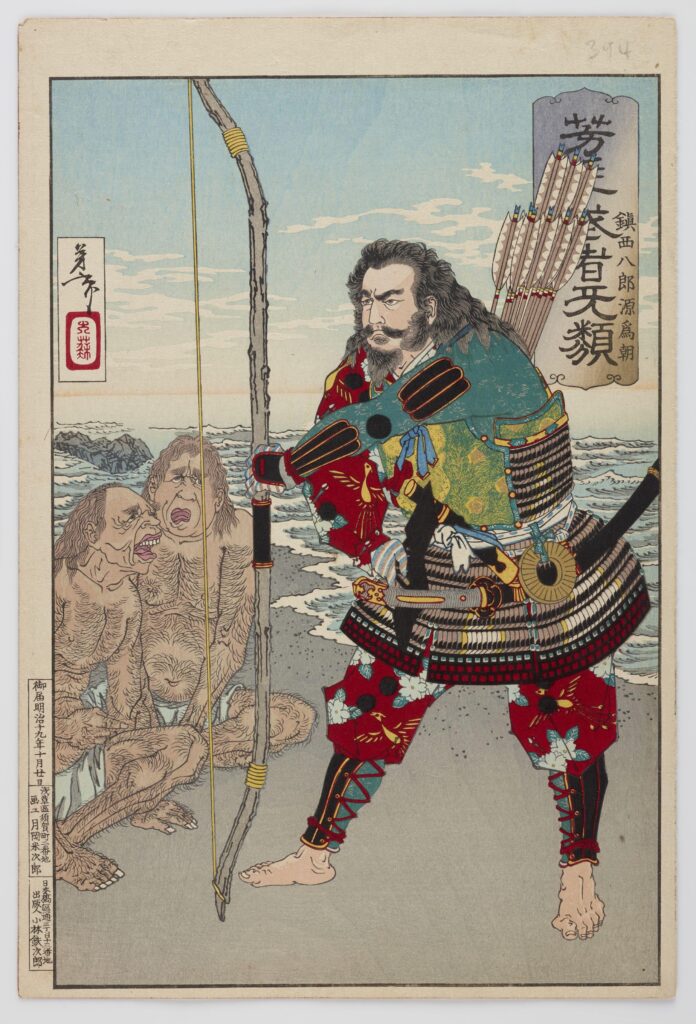

The end of the Heian Period and what was defined as “Classical Japan” would then transition into the Medieval Period which saw the rise of Samurai culture. This would redefine the perception of masculinity and how it would change during wars and affect warfare. The Kamakura Period saw the rise of the Shogun. While it was technically a military position, the Shogun would be considered as the real ruler of Japan. The Medieval Period in Japan is dominated and defined by war. Depictions such as the painting of Samurai Chinzei Hachiro Tametomo show masculinity through strength compared to its softened image during the Heian Period. These shifts in how masculinity is viewed and defined also demonstrates how the concept of Japanese masculinity has been celebrated, challenged, and constantly redefined throughout history.

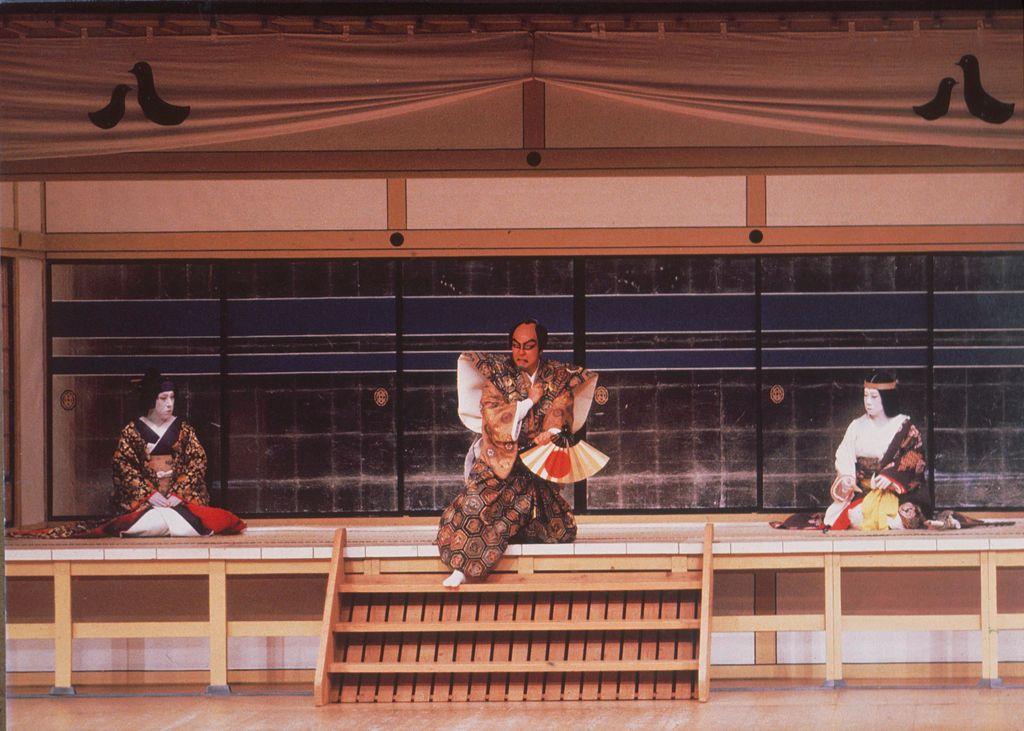

By the Tokugawa era, masculinity underwent yet another transformation, shaped by the prolonged peace under the shogunate’s rule. With the diminishing role of samurai on the battlefield, the ideal of masculinity shifted away from martial prowess and toward the values of discipline, loyalty, and intellectual cultivation. Artistic depictions of masculinity from this period often highlight this duality, portraying samurai not only as warriors but also as refined scholars and artists. Furthermore, the flourishing urban culture of the Edo period brought new interpretations of masculinity through kabuki theater and ukiyo-e woodblock prints, which often depicted dynamic male characters, including actors, merchants, and everyday townsmen, showcasing a more diverse and multifaceted understanding of manhood.

Each piece in this exhibit will provide a window into how masculinity was perceived by Japanese society throughout history. As ideals of masculinity are reshaped in society, court, and on the battlefield, these changes are reflected in the art of the time. This exhibit will use these pieces of art to show how societal conceptions of masculinity have changed over time. From the connections to nature in the Heian period, to the focus on samurai and war in the Medieval Period, to the emergence of masculine femininity in kabuki theater during Tokugawa era, this exhibition will show how cultural ideas of masculinity have changed throughout Japanese history.

EXHIBIT

This triptych of woodblock prints by Japanese artist Kobayashi Kiyochika depicts a male courtier on a moonlight beach during the Heian Period. Made in the Meiji Period, this print highlights the deep connection between Japanese ideas of masculinity and nature during the Heian period. During this period, Japan was still very much a rural nation, with many men interacting with nature on a much greater scale than we see in later periods. There were also differentiations between man’s relationship with nature and social status. For example, the courtier depicted in this image would have seen nature as an artistic and spiritual medium, whereas, many commoners during the Heian Period would have had a more extractive relationship with nature due to their reliance on the land for survival. Kiyochika depicts this relationship with metaphoric images such as the roots of nearby trees intertwining below the feet of the courtier, symbolizing the deep connection between man and nature. Additionally, the intense attention to detail with the moon casting light on the water illuminates the scene, allowing the courtier to find his way across the beach (RISD Museum). The heavy focus on nature in this image echoes the use of nature in Waka poems during the Heian period. For example, the moon and tree in this image both draw connections to seasonal changes as metaphors for human emotion. Something that was extremely common in Heian Period Waka poetry. Kiyochika uses this piece to advance this cultural connection from forms of poetry to painting (Haruo). In doing so, he provides viewers with a more complete understanding of how nature symbolized Japanese culture during the Heian period. Written by Conor O’Hara.

This wood sculpture made in the 12th century depicts a Buddhist deity known as Myōō, or ‘Kings of Brightness’. In the sculpture, the figure is seen holding a sword in his right hand and a reign in his left. As an enforcer and protector of Buddhist law, Fudo Myōō would use his sword to cut through religious ignorance and his rope to reign in those who block the path to enlightenment. The figure’s solid base, strong legs, and broad shoulders imply a sense of strength that refers to the idea that the deity being depicted was immovable and a constant presence in Buddhist practice. Also, these strong features represent the intense masculinity of the figure. This focus on masculine features is quite commonly seen in Heian Period art. This is largely due to the immense value that Heian society placed on the beauty of “masculine” features. During a time when spiritual and intellectual depth were defining features of masculinity and beauty, Heian sculptors and artists used pieces like this to convey the cultural importance of the connection between spirituality and masculinity. This sculpture from 12th-century Japan shows the uniqueness of the cultural conception of spirituality during the Heian period. Masculinity and religious spirituality were intertwined in Heian culture and pieces like this showcase that connection. Written by Conor O’Hara.

This image depicts an episode of the medieval war tale, Heike Monogatari. The man being shown in the image is Taira no Atsumori, a young nobleman who was killed by the Minamoto warrior Kumagai no Jiro Naozane during the battle of Ichinotani. Realizing the battle was lost, Astumori guided his horse into the sea before Kumagai’s challenge forced him to return to land to defend his honor. In this print, we see an abundance of vibrant design despite a limited color pallet. One such example of intricate design is shown with the cloth covering Atsumori’s shoulders. This design is aesthetically pleasing, but shoulder pads would have also protected him from arrows being launched in battle. Atsumori also holds a bow in his right hand, as well as a satchel full of arrows on his back. Clearly, he is prepared for battle. Furthermore, the intricate design of the waves surrounding Atsumori and his horse symbolizes a connection between man and nature that was very prominent during the Heian period. However, the high levels of militarization seen in this piece highlight new values associated with the Kamakura Period. Among these values is the increasing cultural association between masculinity and war. During the Kamakura Period, masculinity was defined by a warrior culture that espoused a doctrine of honor, discipline, and violence. Images like this begin to show the importance of masculinity and honor in battle during the Kamakura Period. Written by Conor O’Hara.

This woodblock print by Utagawa Kunisada, created in 1850, depicts a male actor playing a female character in a Kabuki theater scene. At the time, women were banned from participating in public performances, forcing male Kabuki actors to perform both male and female roles. In this print, the actor’s strong jawline and elongated face reveal his male identity, even though he is dressed in traditional female clothing. The exclusion of women from Kabuki theater reflects broader societal dynamics in Tokugawa Japan. This ban reinforced patriarchal elements within Tokugawa society, limiting women’s roles in public and cultural spheres. Actors like the one in this image who specialized in portraying female roles were known as Onnagata. Their performances marked a significant shift in cultural understandings of gender and sexuality during the Tokugawa period. In Tokugawa Japan, masculinity had evolved from previous periods. Masculinity went from being defined by military prowess to being associated with beauty and male femininity. This print captures this cultural transition, as Onnagata embodied an aesthetic of idealized femininity. When compared with other works in this exhibit, Kunisada’s piece serves as a perfect example of how societal conceptions of masculinity changed over time in Japanese history. Written by Conor O’Hara.

This is a type of Japanese traditional painting, called Ukiyo-É, produced by a renowned artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (active in the early Meiji era). This painting depicts a Japanese warlord called Taira-no-Kiyomori, who was active in the late-Heian period. He was the first samurai to rule the country as a tyrant, known for both his intelligence and military leadership. In fact, in this work, Kiyomori is represented as a strong symbol of masculinity that attempts to even stop the movement of the sun with his hand fan. Kiyomori’s act of attempting to reverse the destiny of a cosmic object underscores his ambition and audacious belief in his own power, an image of a man challenging the natural order itself. This also implies the unprecedented power and strength that he exemplified during the era, symbolizing a shift from conventional transitions of powers within the aristocratic court to assertive leadership and control. His determination to place his family in high-ranking positions, even marrying his daughter to the emperor, marked a dramatic change in the norms of the courtly culture, where the emerging warrior class was gradually gaining power. A small girl standing next to him plays a role of presenting a sense of juxtaposition within the image, contrasting an innocent pure child to a tall, muscular figure just like Kiyomori. Together, these elements create a powerful contrast that emphasizes the weight of Kiyomori’s ambitions and the masculine ideal of strength in an era defined by both aristocratic grace and martial ambition. Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s painting thus captures the complexity of masculine identity in an era where warriors like Kiyomori were reshaping Japan’s political and social landscapes. Written by Kaz Osawa

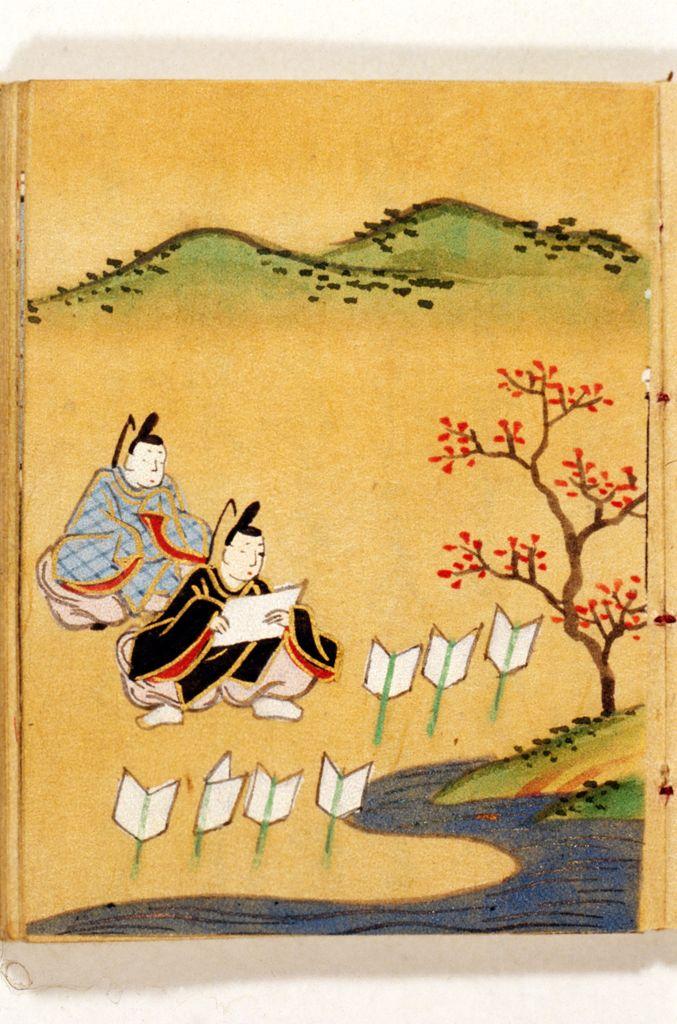

This artifact titled “The Tales of Ise”, exhibits the unique sense of masculinity that became pervasive across the country in the mid-Heian period, especially promoted within the courtly culture. This image reflects the Heian aesthetic of miyabi (courtly elegance) and mono no aware (an appreciation of fleeting beauty), which were core to ideal masculine identity at the time. Men of the Heian aristocracy were expected to be sensitive and thoughtful of natural beauty, expressive in poetry and literature while skilled in courtship, enabling a blend of intellectual strength and refinement. Such a peaceful image of masculinity can be also seen in various other work of art at the time, such as The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shiki-Bu. The male figures in the image, likely representing a courtier or protagonist of “The Tales of Ise”, embody the discussed ideals above. His graceful posture and interaction with the nature (being surrounded by a river, grasses, cherry blossoms, and mountains in the horizon) while engaging in poetry suggest a sense of masculinity that is modest and thoughtful. Unlike the other work depicting Taira-no Kiyomori, a samurai appearing in the late-Heian period characterized physical strength and dominance, delicate brushstrokes and warm atmosphere in the painting aligns with a peaceful understanding of masculinity that puts emphasis on cultural accomplishments and appreciation of nature. Written by Kaz Osawa.

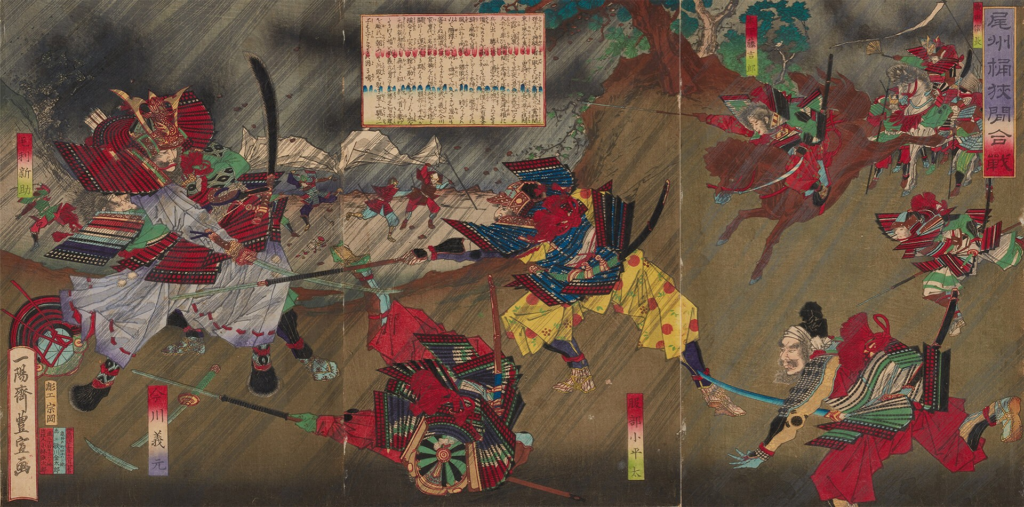

This is an Ukiyo-É painting produced by the renowned artist Utagawa Toyonobu. It depicts the war of Okehazama (Okehazama no Tatakai) in 1560, where the warlord Nobunaga Oda, who was only 27 years old at the time, battled against Imagawa Yoshimoto. In this warfare, Nobunaga with an infantry count of roughly 4,000 defeated Yoshimoto with more than 25,000 soldiers, making it one of the most famous battles of the medieval Japanese history. The precise moment of the painting depicts seconds before Yoshimoto gets executed by three of Nobunaga’s soldiers. If one observes closely to the figure on the left (Yoshimoto), a soldier can be seen behind, about to reach his neck with a katana while the allies confront from the right. The masculinity of the soldiers are represented by vibrant red armours and helmets, use of huge weaponries, as well as their skillful handling of horse-riding at the battlefield. The dark clouds and the slashed lines in the painting (though not certain if this is intended) provides the high-tense ambiance of the war, highlighting the audacity and unwavering strength of the soldiers at the time. Unlike the work of “The Tales of Ise”, where masculinity of courtly cultures were symbolized with the intellectuality to discover beauty in nature (mono no aware), this depiction of the late medieval period is characterized by the modern-alike sense of masculine figures. Written by Kaz Osawa.

During the Warring States period, masculinity was predominantly tied to the warrior class (samurai) and defined by martial valor, physical prowess, and loyalty to one’s lord (daimyo). The nature of chaos and constant warfare necessitated an imagery of masculinity focused on survival and dominance. However, with an establishment of perpetual peace during the Tokugawa regime, the society has diminished the need for such martial masculinity. The rise of Kabuki theater introduced a more performative and fluid vision of masculinity. As female actors were prohibited in the theater at the time, male Kabuki actors (onnagata) played female roles, creating a popular aesthetic of gender ambiguity and challenging rigid masculine ideals. However, on the other hand, Kabuki also celebrated the bravado and charisma of tachiyaku actors who played strong, masculine roles, drawing inspiration from samurai traditions. This duality is vividly captured in the painting, where the actor playing a male role embodies the stoic strength and bold gestures reminiscent of the samurai ideal, while the onnagata actors bring an elegance and grace that blur the boundaries of gendered performance. The juxtaposition of these figures illustrates how Edo-period masculinity was not a singular construct but a dynamic interplay between tradition and innovation. Written by Kaz Osawa.

This painting by Yashima Gakutei (1786?-1868) depicts famous calligrapher Ono no Tofu (894-966). Following the end of the Nara period Japan transformed into what is considered their last “golden age” which is known as the Heian Age. This is considered as the “golden age” because of how it was dominated by a development in artwork, literature, and a refined courtly culture. This period saw the Fujiwara Clan “succeed in dominating the royal family by marrying female clan members to emperors and then ruling on behalf of the offspring of these unions when they assumed the throne”. (Metropolitan Museum of Art 2002) The Fujiwara clan led unopposed and under their rule Japan began a new golden age with esoteric buddhist influence which gave a new aspect and importance to beauty and elegance. Ono No Tofu was born 100 years into the Heian period and is known for his role as a calligrapher. This art-form was prominent during the Heian period as the courtly class “placed high value on beauty, elegance, and proper manners”.(Metropolitan Museum of Art 2002) These traits were often associated with masculinity’s perception during the period. Masculinity in this image is defined more by one’s manners compared to physical strength. There is no distinction of muscles or traditionally “manly” features rather the focus is on what the Ono no Tofu is doing. At the end of the Heian period showing physical strength would become the source of power/influence as samurai increased and into the eventual Shogunate period. Written by Drew O’Connell.

Above, this painting depicts Samurai Chinzei Hachiro Tametomo (1139-1170). Although known as a Samurai he was most known for his strength as an archer. The end Heian period saw the fall of the aristocratic Fujiwara clan and a transition into the Shogunate which is known for its warlord rule. Tametomo’s depiction is one of strength and his figure is particularly brawny. This comes from his legends which tell of how “his drawing arm was reputed to be four inches longer than his other, and he had sunk a Taira ship with a single arrow”(Museum of New Zealand 2024). This fame came from his service under Emperor Sutoku “with minamoto forces against those of Taira no Kiyomori and his own brother Yoshitomo in the Hōgen Rebellion of 1156”. (Museum of New Zealand 2024) The Taira clan emerged victorious and as punishment for his participation in the war the “Taira cut the sinews of Tametomo’s left arm and exiled him to the island of Ōshima”. (Museum of New Zealand 2024) The event to note in his life after being exiled was his suicide. Tametomo committed seppuku in 1170. It was one of the first recordings of seppuku which is defined as “ritual suicide by disembowelment with a sword, formerly practiced in Japan by samurai as an honorable alternative to disgrace or execution”. (Oxford Dictionary 1856) The artist’s choice of Tametomo is because of his tales and how he represents masculinity as strong. Strength through power marked the end of the Heian period which was known for being the last classical age for Japan and into the Shogunate and the increase of samurai and warfare in Japan. It should also be of note that the two other humans in the painting are not directed with Tametomo but with the artist Yoshitoshi’s personal views. Written by Drew O’Connell.

The image located above is of a spear that is dated from 1500-1800. This spear was used in combat and one of the major themes in the medieval period is the development of combat and how it influenced the perception of masculinity. This era saw the samurai and the warrior class begin to rise along with increasing military conflict. In 1351 Ashikaga Takauji established the hanzei which meant that half of a province’s tax revenues were reserved for military use. With an increased budget for military use, so did the frequency of war. During the Warring States Period, power was achieved through violent conquest rather than diplomacy. How people view masculinity in war is often through the action’s of individuals. Masculinity during war is associated with courage, honor, discipline while cowardice and dishonor were viewed as shameful acts. The spear shown above represents how masculinity’s perception of strength/conquest at the time would develop new war tactics. Pike formations which would utilize these spears were first recorded in 1454. Development of combat strategy led the samurai to have increased training with each other as a unit rather than individuals. This brought the soldiers closer together and contributed to a stronger sense of brotherhood. One of the central products of war is how it expands what is considered to be “masculine”. Written by Drew O’Connell.

This image created in the early 19th century depicts Europeans, specifically the Dutch and their arrival on the Japanese island of Deshima located in Nagasaki harbor. The Dutch were eventually permitted by the Tokugawa Shogunate to step foot on the mainland and eventually conduct commerce with the Japanese merchants. On the way to the capital of Edo, the Dutch procession was required to pay homage to the Shogun by wearing traditional Japanese costumes. During the Tokugawa Shogunate, symbols were one of the greatest demonstrations of power. By having Dutch merchants march to the capital to meet with the Shogun while wearing costumes displayed a clear message of the Shogun’s strength/authority to the arriving Dutch. Japanese artists depicted the Dutch with bland outfits and the only bright colors come from those donning Japanese clothing. After the Warring States Period, the Tokugawa shogunate would designate the samurai as a new immobile class. This led to masculine ideals such as strength and power to be shown through class rather than violent conflict like the Warring States Period. In this image the strength is shown by the Shogun from his demands to meet with the arriving Dutch merchants. Eventually, commerce between Dutch merchants and Japanese merchants began and so did the trading of knowledge. These merchants played a significant role in the spreading of “practical knowledge” which mainly focused on medicine, botany and natural history. “Dutch Studies” then developed from the wide range of available subjects based on European texts written in Dutch at the time as a competing school in Japan. Written by Drew O’Connell.