Throughout Japan’s history, Buddhism and Shinto have played key roles in the development and proliferation of politics, culture, and traditions. In the early years of the country’s history, there was no organized religion, rather local deities (‘kami’) that aggregated their own cults in different regions. These loosely connected kami were organized in a certain hierarchy, with each bearing their own importance, with one of the most revered deities being Amaterasu who was said to be the ancestor of all emperors. Unlike Buddhism, what we now call Shinto did not have its own schools of thought and its teachings were not secretive like that of esoteric Buddhism, which were reserved for the highest ranks of society. Shinto as we know it now is often a projection into the past by the priests and theorists inside the religion, as well as historians, retrospectively as opposed to the more fragmented, localized religion it was during the Nara and Heian periods.

Shinto was the ‘indigenous’ foundation for many of the creation myths of the country that appeared in seminal historical texts, based on the environment and geography of the country. Buddhism, on the other hand, was exposed to Japan around the sixth century through continued diplomatic interaction with the continent, notably Paekche (modern day Korea) and China. It became a favorite amongst several emperors for its civilized associations with China, and became an elitist religion, especially the selective esoteric Buddhism (reserved for the imperial court and high-class families). Buddhism then became a state religion in the Nara period and continued to be influential through the early modern era. Its teachings and sacred mantras guided the development of culture and literature. These socioeconomic and religious values influenced the nature of art produced in Japan, including its mediums (poetry and visual art) and themes (impermanence and enlightenment).

During the medieval period, the differences outlined above between the two religions began to fade as Buddhism and Shinto converged. Shinto beliefs were restructured as Buddhist deities were assigned corresponding local Japanese kami and kami were theorized to be the manifested forms of Buddha. Shinto texts and rituals were formalized around Buddhist models, and shrine complexes were built to combine the Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines in one place. Their intertwined nature meant that the practice and ideology of one often involved another, making them inextricably connected in this period. Both religions, particularly Zen Buddhism, remained relevant in solidifying power and emerging warrior clans and classes were significant patrons of temples and were heavily aligned with faith-based values.

However, in the early modern period with the arrival of the Tokugawa shogunate, the role of religion changed from that of the prior periods. Citizen’s registration at Buddhist temples was monitored; the shogunate heavily controlled the religious organizations in order to suppress their power (a departure from the great influence of religion and its figures in politics and society). Foreign religions like Christianity were repressed, also vastly different from the praise of foreign influence earlier in the country’s history. With the repression of religion and the emphasis on other elements of daily life, art seemed to similarly deemphasize religion and depicted more scenes of everyday life (particularly following the lives of samurai and other elites).

Throughout this exhibition, the artworks reflect the evolution of Shinto and Buddhism in Japanese history from the Nara period into the early-modern period. Their respective origins, the difference between the indigenous and foreign roots, provided for different trajectories in broad culture as well as art. However, both religions were used by the imperial house and the shogunate for their own political and social gains, and thus parallels can be drawn. As demonstrated by the selected works, expensive materials, often involving imported silk and gold, reflect the elitist nature of art in Japan at the time, for both Shinto and Buddhist themes. And while the themes differ depending on the values of the religion, their broader historical context, and their place in the imperial court and the shogunate, there are more similarities than may be evident upon first glance.

The frontispiece of this scroll depicts the “Devadatta” chapter of the Lotus Sutra (1). Sutras were very important to Buddhism because they were scriptures that encapsulated the teachings of Buddha. As time went on, the works of Shinto faded as Buddhist ideas inserted themselves and in future concepts “Buddhism practically excludes Shinto” (2). The first mention of the Lotus Sutra is not until the time of Shotoku Taishi in 574. However, the devotion to the Lotus Sutra began in the Nara period among the aristocracy. Eventually, the sutra took hold among the ordinary people This sutra was recited as part of a religious practice in order to “rid the land of karmic evils accumulated since beginningless time.” (3) The Lotus Sutra promises salvation to all those who believe in which they will receive a karmic reward.

Specifically, this image depicts the twelfth chapter of the Lotus Sutra which teaches that both women and evil persons are capable of achieving Buddhahood, which had been previously denied in other teachings. In Chapter 12 of the Lotus Sutra, there is a story about an eight-year-old girl achieving enlightenment (4). In the image, there is a girl kneeling in front of a group offering a jewel to the Buddha on Eagle Peak. At the heart of the image, the jewel radiates a brilliant glow, providing emphasis on the importance of her offering. The jewel represented the Dragon Girls offering in order to achieve immediate Buddhahood. This image demonstrates that Buddhahood is attainable regardless of age or gender, that all people are capable of it. The Lotus Sutra set the foundation for new directions Buddhism would go in the medieval age. (Written by Caroline)

(1) Lotus Sutra, Chapters 12 and 14. 1667. Two handscrolls; gold, silver on indigo-dyed paper. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/54782.

(2) Meshcheryakov, A. N. “The Meaning of ‘The Beginning’ and ‘The End’ in Shinto and Early Japanese Buddhism.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 11, no. 1 (1984): 43–56. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30233311.

(3) Takashi, Nakao, and Wayne Shigeto Yokoyama. 1984. “The Lotus Sutra in Japan.” The Eastern Buddhist 17 (1): 132–37.

(4) “‘Devadatta’ Chapter | Dictionary of Buddhism | Nichiren Buddhism Library.” n.d. Accessed November 1, 2024. https://www.nichirenlibrary.org/en/dic/Content/D/34.

Artwork: “『妙法蓮華経』 「提婆達多品第十二」 / ‘Devadatta,’ Chapter 12 of the Lotus Sutra (Hoke-Kyō, Daibadatta-Bon): ‘Devadatta,’ Chapter 12 of the Lotus Sutra (Hoke-Kyō, Daibadatta-Bon) [65.216.1].” n.d. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://jstor.org/stable/community.18476488.

Buddhism was not introduced to Japan until about 552 when a Paekche diplomatic mission presented a Buddha statue and several sutras to the Yamato court (1). Originally Buddhism was seen as a threat to their indigenous beliefs as it was the structure for their political and social order. The adoption of Buddhism sparked several military conflicts, but by 587, it had gained official recognition from the court. After its adoption, Buddhism created an atmosphere that opened up Japan’s willingness to accept foreign ideas about their social and political systems. Buddhism was likely brought over by Korean immigrants and provided greater sophistication with a writing system, architecture, and tools for a centralized state from a significantly more advanced country, China (2). Over a century later, Tenmu and Jito ascended to power transforming the imperial power. Under their reign, they used Buddhism as a way to unite people under a shared culture. More specifically, Tenmu followed the “Sutra of Golden Light” that complemented his divine right to rule. Buddhism became the main religion of the state in 749 with the Building of Todaiji a temple outside of Nara. As the main temple in the national system of monasteries called Kokubun-ji, the temple was the center for rituals of peace and prosperity and central for the training of monks studying Buddhism (3). This temple is still a place where traditional Buddhist rituals are performed.

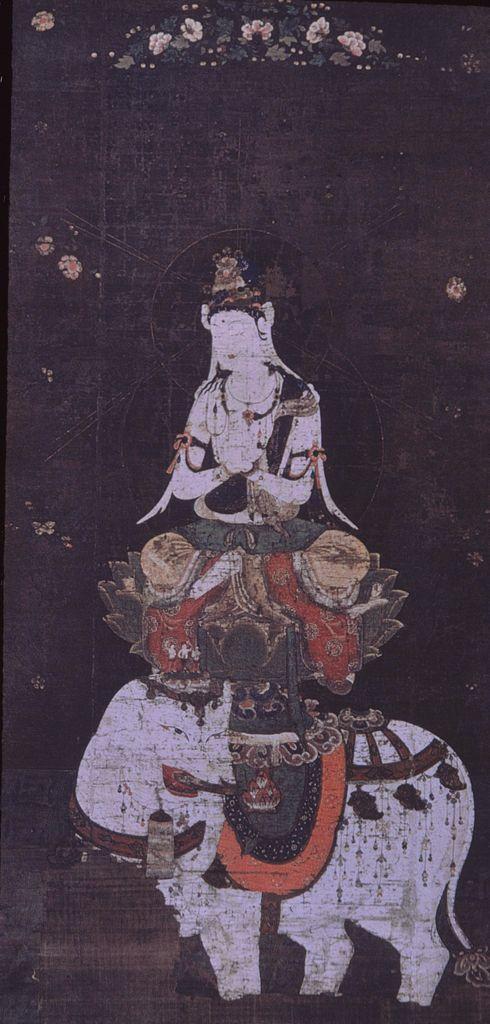

This Bodhisattva Samantabhadra, who is one who seeks awakening but delays their ascension to enlightenment out of compassion, is displayed sitting on a six-tusked elephant (4). This elephant can be seen as a symbol of the full accumulation of virtue gained through the Buddha’s spiritual efforts across his past lives. Samantabhadra appears in the Lotus Sutra and is described as advancing to earth, riding a six-tusked elephant, as shown in the illustration and is referred to as the protector of the Sutra (5). Overall, Buddhism became a vital aspect of the state, and this depiction highlights the importance of Samantabhadra as a guardian of the Lotus Sutra and a symbol of virtue in Buddhist traditions. (Written by Caroline)

Footnotes:

1. Adolphson, Mikael S. 2012. “Aristocratic Buddhism.” in Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850, 135-145. Westview Press.

2. Adolphson, Mikael S. 2012. “Aristocratic Buddhism.” in Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850, 135-145. Westview Press.

3. “History – 東大寺.” 2022. March 7, 2022. https://www.todaiji.or.jp/en/history/.

3. Lopez, Donald S., and Jacqueline I. Stone. “Encouragement of the Bodhisattva Samantabhadra.” In Two Buddhas Seated Side by Side: A Guide to the Lotus Sūtra, 258–62. Princeton University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvfjczvz.29.

4. “Bodhisattva | Buddhist Ideal & Path to Enlightenment | Britannica.” n.d. Accessed November 1, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/topic/bodhisattva.

5. Lopez, Donald S., and Jacqueline I. Stone. “Encouragement of the Bodhisattva Samantabhadra.” In Two Buddhas Seated Side by Side: A Guide to the Lotus Sūtra, 258–62. Princeton University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvfjczvz.29.

Artwork: Samantabhadra. Mid 12th C. https://jstor.org/stable/community.13592678.

This two-panel folding screen created by Suzuki Shuitsu in the Edo or Meiji period (unclear) is a prime example of a reflection of Shinto into the past, exhibited in the work of historians and artists alike. It depicts a scene from the fourteenth century war epic “The Tale of the Heike”, which the story of the twelfth century (tail end of the Heian period) warrior Taira no Tsunemasa (2). In this scene we see the warrior play the biwa, a wooden lute that is traditionally used in narrative storytelling (1). The instrument gained popularity in China, eventually reaching Japan during the Nara period (1), showing the extent of Chinese influence in the cultural and artistic traditions of Japan. The warrior, in rich garb, plays for the kami Chikubushima that is metamorphosed into a white dragon. The story depicts Tsunemasa, having traveled from Kyoto to join the forces against the Minamoto army in eastern Japan, stopping at the Tsukubusuma Shrine and playing music as a form of offering (2).

The scene is simple, with an emphasis on the warrior and his lute in the forefront, and the dragon backdropped by the moon above. The colors are otherwise sparse, highlighting the importance of the two main figures: Chikubushima and Tsunemasa. At this point in time, warriors were gaining prominence and power, becoming part of a ruling class in their own right. To pay tribute to a kami before battle demonstrates that Shinto beliefs have remained important in the Heian period amongst the elite members of Japanese society. However, unlike the Nara period, they have come to play a far larger role in organized violence than ever before in Japanese history. This mirrors Buddhism’s role during the Heian period, and how both religions in Japan were very much political weapons.

Moreover, the moon shining above is significant and beloved as a key symbol in Japanese culture and the Shinto traditions, embodying ‘yin’ qualities – the feminine and the dark. It embodies the positive aspects of the night sky, including dreams and energy balance. Moreover, the lunisolar calendar that came to prominence in the Nara period and reflected the authority of the heavens (which was bestowed upon emperors by the gods) also comes into play here. A full moon is seen her, a symbol of completeness and in alignment with the rhythm of the moon calendar. This emphasizes that there is harmony in the sky, and thus the heavens and kami are pleased by the warrior and bless him for his future battle. (Written by Antonina)

(1) Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “biwa”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 2 Jan. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/art/biwa. Accessed 31 October 2024.

(2) Artist: Suzuki Shuitsu, Japanese, 1823-1889. Taira no Tsunemasa Playing the Biwa at Tsukubusuma Shrine. Two-panel folding screen; ink, color, and gold on silk, second half of the 19th century. Lent by Feinberg Collection to Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/78487. Accessed 31 Oct. 2024.

This screen dating to the Edo-Meiji period by Mori Kansai depicts a secluded shrine in the mountains of north Kyoto (2). This distanced location is typical of Shinto shrines that were rarely within the confines of the city in the Nara and Heian periods, unlike the Buddhist temples. It is the oldest Shinto shrine in Kyoto, the former Japanese capital, and one of the oldest shrines in the country (1). The shrine is dedicated to the kami Kamo-wake-ikazuchi, who is said to have descended there (1).

The legend of this shrine involved the daughter of the Kamo clan, who became pregnant by the power of a divine arrow and bore a son that then became Kamo-wake-ikazuchi (1). The Kamo clan is also associated with the deity Kamo Taketsunumi no Mikoto, that served as the guide to Emperor Jinmu (1). This story emphasizes the desire of elite families to align with the divine. Doing so, just like the imperial family that claimed to descend from Amaterasu, would allow them to similarly establish and explain their power. Such incentive may be in part why religious institutions such as the Kamigamo shrine could have been constructed and certainly why they were revered.

The shrine itself was constructed in 677 and over the years saw many visitors, particularly from emperors that saw it as a protector of the imperial court (1). During the Heian period, it became one of the highest ranked shrines in the country and received official patronage from the imperial court, then followed by the powerful warrior clans (1). Imperial patronage allowed for the court to exert their ‘divinely bestowed power’, but also to justify their actions since they supported the shrines of the gods. Sites like the Kamigamo shrine demonstrate that religion in both the Nara and Heian periods were nearly impossible to separate from the state and had a strong reciprocal relationship.

The colors are soft, and the picture is shrouded in mist, as though protecting the shrine and the torii gate. The picture makes quite clear that the shrine is elevated, away from society, making it almost pristine and divine in its depiction. The image is rich, one befitting a shrine that was revered by the emperors and sits upon land touched by a kami. (Written by Antonina)

(1) “About Kamo Wakeikazuchi Jinja Shrine.” Kamo Wakeikazuchi Jinja Shrine (Kamigamo Jinja), www.kamigamojinja.jp/en/about/. Accessed 31 Oct. 2024.

(2) Artist: Mori Kansai, Japanese, 1814-1894. Kamigamo Shrine in Summer. ink and gold wash on paper with hints of color, 1860-1870. The Walters Art Museum; Museum purchase with funds provided by the W. Alton Jones Foundation Acquisition Fund, 1989; 35.147; [Dealer], Osaka; Toyobi Far Eastern Art [Dr. Frederick Baekeland and Joan D. Baekeland], 1987-1988; Walters Art Museum, 1989, by purc, JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.15706176. Accessed 31 Oct. 2024.

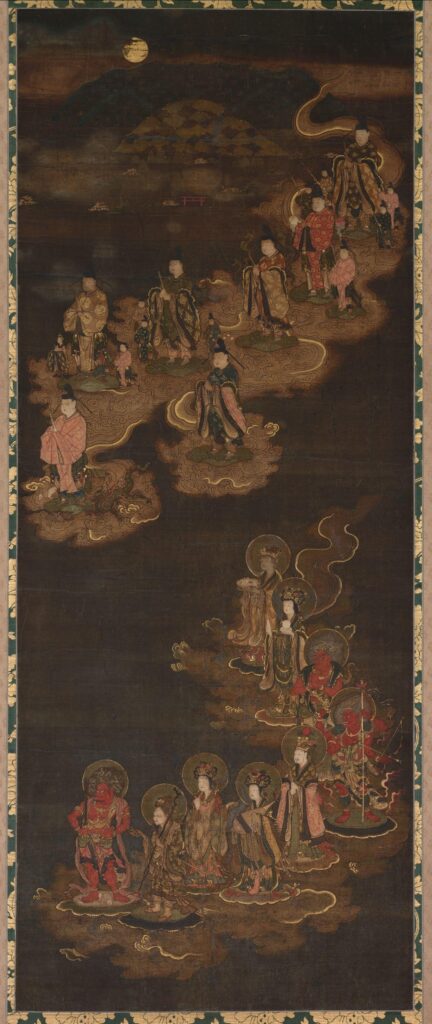

This hanging scroll painting portrays celestial beings descending from the heavens into the Kasuga Shrine in the ancient capital of Nara (1). This shrine was officially founded 768 as a shrine to ancestors of the Fujiwara Clan (2). In the medieval period, when this painting was produced, it represented the convergence of Shinto and Buddhism and was used to generate an image connected to the worship of celestial bodies in esoteric Buddhism (3). At the uppermost portion of the painting there is a torii gate (entrance to a Shinto shrine), the Kasuga Mountain range, and the moon, which has long been the symbol of enlightenment in Buddhism, paving the way for the luminaries and stars to descend (4). The nine luminaries and the seven stars in the painting represent many celestial symbols. Five of the luminaries represent the actual planets of Jupiter, Mars, Saturn, Venus and Mercury, while the other four represent the sun, moon, and other cosmic beings. Additionally, the stars create the Big Dipper constellation, which is known as Hokuto Shichisei in Japanese. This constellation represents the first kami, Amenominakanushi, in Shinto traditions and a symbol of the Bodhisattva Marici in Buddhist traditions (5). The seven stars symbolize a shared cosmological framework, reinforcing the deep connection between Shinto and Buddhist beliefs depicted in the painting.

Religious shifts were occurring throughout the medieval period with the emergence of new forms of exoteric and esoteric Buddhism that connected Buddhism and Shinto. The vertical hierarchy starts at the top with cosmic Buddhas, who serve as the ultimate providers of salvation. It extends downward through various beings, including local Buddhas and deities, many of whom are enshrined in local temples such as the Kasuga Temple (6). This image appears to illustrate the convergence of cosmological Buddhism and local Shinto kami in medieval Japanese religion. (Written By Caroline)

(1) “Descent of the Nine Luminaries and the Seven Stars at Kasuga.” Cleveland Museum of Art. Description of artwork. Accessed November 29, 2024. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/2015.63.

(2) Cali, Joseph, John Dougill, and Geoff Ciotti. “Kasuga Taisha.” In Shinto Shrines: A Guide to the Sacred Sites of Japan’s Ancient Religion, 160–63. University of Hawai’i Press, 2013. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqfhm.29.

(3) “Descent of the Nine Luminaries and the Seven Stars at Kasuga.” Cleveland Museum of Art. Description of artwork. Accessed November 29, 2024. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/2015.63.

(4) “The Significance of the Moon in Japanese Culture.” n.d. Nihongo Master. Accessed November 29, 2024. https://www.nihongomaster.com/blog/the-significance-of-the-moon-in-japanese-culture.

(5) “Muza-Chan’s Gate to Japan.” n.d. Accessed November 29, 2024. https://muza-chan.net/japan/index.php/blog/japanese-zen-gardens-the-seven-stars-of-hokuto-shichisei.

(6) Adolphson, Mikael S. 2012. “Medieval Religion” in Japan Emerging, 226. Westview Press. https://ctw-tc.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay/alma9931930205103767/01CTW_TC:CTWTC.

Artwork: Descent of the Nine Luminaries and the Seven Stars at Kasuga / 北斗九曜春日降臨図. mid- to late 1300s. Hanging scroll; ink, color, gold and cut gold on silk, Mounted: 184.5 x 58.5 cm (72 5/8 x 23 1/16 in.); Painting only: 106 x 42 cm (41 3/4 x 16 9/16 in.); with knobs: 184.5 x 63.5 cm (72 5/8 x 25 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art; Cleveland, Ohio, USA; Collection: ASIAN – Hanging scroll; Department: Japanese Art; Provenance: description: (Piasa Auction house, Paris, France, June 13, 2014, Lot. 261, sold to Leighton R. Longhi Inc.); date: June 13, 2014; description: (Leighton R. Longhi Inc., New York, NY, sold to the Cleveland Museum of Art); date: 2014-15; description: The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH; date: 2015-; Lillian M. Kern Memorial Fund. https://jstor.org/stable/community.24628456.

This 17th century handscroll depicts what looks like a beautiful young woman and a Buddhist monk. However, the picture is not as it seems, instead the women is a fox (3). The monk, who must have taken a vow of celibacy, cannot resist temptation. In the medieval ages, art in Japan was a medium to preach good morals (3). These morals were often based on Buddhist tenets and teachings. In Buddhism, for monks and nuns, sexuality must be abandoned to achieve enlightenment through suffering (2). A handscroll such as this one is one of the methods used in Japan to spread these religious messages and teachings.

However, this is not just a Buddhist picture as the second key figure apart from the monk is the disguised fox. The fox in Japanese folklore and Shinto religion is a figure that possesses high intelligence and stands for longevity (1). They are Inari’s (a god associated with rice, tea, and sake) chosen messengers, thought to be guardians that ward off evil spirits (1). However, they are also known for their tricks and deceit. In traditional folklore, they fool those who have been immoral to punish them for ills such as greed, often in the form of metamorphosing into a beautiful woman (1).

This type of mischief is depicted in this scene, adding another element of morality to the picture. There is the monk who is falling prey to the deluding fox, and thus exhibiting immoral behavior. But there is also an underlying idea that the monk must have acted immorally previously to this to have a messenger fox sent to him. It can be seen here through this juxtaposition that the values of Shinto and Buddhism merge in this scene, and how much the religions had merged at this point in time. It is a partnership between the two religions, preaching morals through art. However, one religious figure deceiving another may be pointing to a hidden message that Shinto and Buddhism were not as congruent as it seemed. (Written by Antonina)

(1) Martin, Roland. “kitsune”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 28 Mar. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/topic/kitsune. Accessed 9 December 2024.

(2) Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “brahmacharya”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 4 Oct. 2013, https://www.britannica.com/topic/brahmacharya. Accessed 17 November 2024

(3) Artist: Unidentified painter and calligrapher, Japanese. Tale of the Fox (Kitsune no soshi). Handscroll; ink, color, and gold on paper, 1669. Collection in Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/845140

This folding screen in ink, color, gold and mica produced by the Kano school, a family of artists whose painting style dominated Japanese art for four centuries (3). The first Kano was of the samurai class and an amateur artist, and his son then solidified the style (3). The school came to be in a time where Chinese cultural ideals were widespread (during the Muromachi period) and thus there are influences in ink technique and subject matter (3). However, the form of expression was uniquely Japanese with the sharps outlines, Japanese landscape and strong brushstrokes. This image demonstrates the key intersections between Chinese influence, a unique Japanese style, and the emergence of a formal school (which was new to Japan) that served the elite samurai class.

The screen depicts Kyoto brimming with all types of citizens, samurai, monks and court ladies alike taking a walk (likely in the spring as the trees are blossoming). The scene shows a Buddhist temple on the right and a Shinto shrine on the left, a marriage of religions in the capital of culture. The central figures are the samurai, in rich garb, which is befittting the expensive nature of the piece (as it is delicately crafted and covered in lush gold). The emphasis on class is seen here through the focus on the elite, samurai class, which promotes the hierarchy that existed during the Tokugawa period.

However, it also shows the harmony that has finally befallen the country. After centuries of warring and civil unrest, this painting is a symbol of unity, both religiously and socio-economically. Moreover, this work is a call to its past and roots, with the inclusion of blossoming trees and gold clouds, which in Shinto religion represents the chariots of the deities to connect them to the human realm (2). The inclusion of these clouds may indicate that the heavens would be pleased with the peace and current activities seen in the scene. This recourse to historic religious and artistic symbols demonstrates the commitment to Japanese traditions and how the country has distinguished itself uniquely. (Written by Antonina)

(1) Artist: Kano School. “Amusements at Higashiyama in Kyoto.” Amusements at Higashiyama in Kyoto [2014.491.1, .2], Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, gold, mica, and gold leaf on paper, ca. 1620s. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.18570402. Accessed 9 Dec. 2024.

(2) Paulson, Aaron. “Summer Clouds in Japan.” Medium, Digital Global Traveler, 13 Aug. 2023, medium.com/digital-global-traveler/summer-clouds-in-japan-7c6e8eea6195#:~:text=In%20some%20legends%2C%20clouds%20act,of%20an%20important%20celestial%20event. Accessed 09 Dec. 2024.

(3) Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Kanō school”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 29 May. 2018, https://www.britannica.com/art/Kano-school. Accessed 8 December 2024.

These early 17th century sliding doors, which have been remounted as a two-panel folding screen show the Torii gate of the Gion shrine, present day Yasaka Shrine (1). The scene, set in Kyoto, shows ornately dressed locals of various classes attending the shrine, perhaps for some festive occasion. At the gate, vendors are selling various domestic goods such as fish and rice cakes to the shrine attendees (1). This demonstrates both the intermingling of the classes as well as the growing importance of trade and domestic production of a variety of goods.

Street markets were a critical part of life in cities like Kyoto and Edo, that relied on the mobility of samurai. Samurai were required to spend part of their time in Edo as part of the alternative attendance system, and many spent extended periods of time in Kyoto as well. The movement of samurai kept the economy afloat, and was a large portion of the money that circulated in the domestic economy. These types of street markets allowed for an entire powerful merchant class to establish itself. Those that received patronage from the elite samurai families gained significant power, mostly due to the political connections as well as the money that came from that kind of work.

This work merges the other growing aspects of Japanese life, and how they were set in religious settings. The scene is religious in a sense that it shows a Shinto shrine (which has assimilated Buddhist characteristics in its architectural style), but it isn’t a simply religious scene. This symbolizes the development of culture and society beyond religion, into production, artisanship and trade. The religious traditions and settings here have become the background rather than the focus of the work. This is a move away from the religious-only focus o folder Japanese art, and now into depicting regular life of Japanese citizens. (Written by Antonina)

(1) “The Torii Gate of Gion Shrine.” At the Shrine Gate [60.164], Sliding doors (fusama) remounted as a two-panel folding screen; ink, color, and gold on paper, early 17th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.34625810. Accessed 9 Dec. 2024.

This hanging scroll made of gold on silk is an early-modern representation of some lingering connections between Buddhism and Shinto. This is an expression of the “Japanese Buddhist concept of “original ground and flowing traces” (honji-suijaku) in which Japanese deities, known as kami, are considered to be manifestations (“flowing traces”) of Buddhist deities (“original ground”) (1). Stemming from a medieval ideal, this early modern iteration includes the seven kami of the Upper Sanno shrines in their original Buddhist forms, while also including kami along the bottom. This shrine is located near Mt. Hiei in northeast of Kyoto, which was considered one of the largest Buddhist institutions at the end of the medieval period (2). The Enryakuji Temple had monks that became founders of other sects of Buddhism such as, Pure Land, Zen, and Nichiren (3). This mandala represents the shrine where Saicho founded the Tendai school of Buddhism. The Tendai school of thought contributed to religious life and advanced the ideas of unity and harmony to a national extent (4). Although Buddhism and Shinto were interconnected during the medieval period, the early-modern period saw Shinto emerging into a more independent identity. Shinto shrines became Buddhist temples, or in the case of this painting, the Shinto shrines now existed within Buddhist temples and were all under the influence of Buddhist ideas. (5) While Buddhism and Shinto were interconnected during the medieval period, the early-modern era saw Shinto gradually developing a more independent identity, even as paintings like this mandala retained elements of their shared beliefs. (Written by Caroline)

(1) Mandala of the Sannō Shrine Deities. 17th century. Hanging scroll; ink, and gold on silk. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45631.

(2) Adolphson, Mikael S. 2012. “Religion in Early Modern Japan” In Japan Emerging, 378-390. Westview Press. https://ctw-tc.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay/alma9931930205103767/01CTW_TC:CTWTC.Japan Emerging- Religion in Early Modern Japan

(3) “Enryakuji Temple (Hieizan).” n.d. Accessed December 11, 2024. https://www.japan-guide.com/e/e3911.html.

(4) Hazama, Jikō. “The Characteristics of Japanese Tendai.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 14, no. 2/3 (1987): 101–12. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30233978.

(5)Hur, Nam-lin. n.d. “Buddhist Culture in Early Modern Japan.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. Accessed December 11, 2024. https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-70?d=%2F10.1093%2Facrefore%2F9780190277727.001.0001%2Facrefore-9780190277727-e-70&p=emailAY0bGt4rUyZhQ.

Artwork:

Mandala of the Sannō Shrine Deities. 17th century. Hanging scroll; ink, and gold on silk. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45631.

This folding screen represents a depiction of the Sumiyosi Grand shrine, originally for Shinto deities whose purpose was to protect seafarers of all ilk, including merchants and even ambassadors to China (1). The crowded scene shows people engaged in various activities, from trading goods and fishing to congregating in social groups, highlighting the shrine’s role as both a spiritual and cultural hub. This image illustrates a different purpose for the shrine, more as a setting for the socioeconomic shift depicted by the merchant class gaining a tremendous amount of power during the Tokugawa period because of social mobility and their connections with elite families (2). Merchants during this period made up the urban commoner society and ranged from wealthy with large shops to simply making a small living. This image depicts a wide range of merchants as there is one with a stall while others are carrying their large cases on their backs. The Tokugawa period saw a large shift of an emerging merchant class, further emphasizing that art was depicting that daily life uses the shrine as a setting instead of making it a religious focus.

Since this shrine was specific to protecting those in the ocean, that can explain the multitude of boats and seafarers in the top corner. This shrine was also known for its close ties with poetry, the performing arts, and sumo wrestling (3). Even though this was primarily a Shinto shrine, Buddhism still played an essential role throughout as it coexisted for so long before and had only just begun to create a separate identity. This shrine reflects the pre-modern coexistence of Shinto and Buddhism, shaped by the honji-suijaku concept, where Shinto deities were considered manifestations of Buddhist ones (4). Additionally, the depiction of the torii gate, only partially shown under the clouds, suggests a shift in emphasis as the religious purpose of the shrine and more of a vehicle for commerce and socialization. (Written by Caroline)

(1) Unidentified artist. Sumiyoshi Taisha Screen. Early 17th century. Six-panel folding screen; ink, color, silver, and gold leaf on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed December 11, 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/902216.

(2) Adolphson, Mikael S. 2012. “Urbanization, Trade, and Merchants.” in Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850, 360-361. Westview Press.

(3)“Sumiyoshi Taisha.” n.d. Sumiyoshi Taisha. Accessed December 11, 2024. https://www.sumiyoshitaisha.net/en/.

(4) Unidentified artist. Sumiyoshi Taisha Screen. Early 17th century. Six-panel folding screen; ink, color, silver, and gold leaf on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed December 11, 2024. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/902216.