Evolution of Buddhism in Pre-Modern Japan

Introduction to the Exhibit:

The exhibition “The Evolution of Buddhism in Premodern Japan” follows the dynamic evolution that followed from its arrival at the mid-6th century to the dawning of the 17th, commonly referred to as the Edo period. It explores the adaptation of Buddhist philosophy, practice, and art in Japan’s cultural and social landscape, indicating how this religion developed into an important part of Japanese identity. This demonstrates the major themes that show the resilience and changing aspects within the Buddhist teachings and the influence which Buddhism has on Japanese culture.

Buddhism first arrived in Japan from the Korean peninsula during the Asuka period, a time of immense cultural change that spanned from 538 to 710. Early exhibits show how new religious inspiration, coming from the introduction of Buddhist texts, imagery, and relics due to diplomatic exchange, stirred on its own behalf the emergence of new architectural, artistic, and literary forms. Through sculptures, paintings, and other artifacts, visitors might trace how Buddhism, immediately on its arrival, was tied to the Japanese imperial court, including in the light of the construction of temples and the use of Buddhism as a political tool of legitimacy. Starting with the Nara period, the roots of Buddhism in Japan began to take shape in more concrete ways, including the rise of powerful schools of teaching. During this period, Buddhist temples were the center of learning and political power.

This development is underlined by this exhibition, with duplicates of the famous Todai-ji Great Buddha statue and other relics of this era, illustrating the role of Buddhism as a force for social cohesion and intellectual advancement. The Heian period, beginning in 794 and lasting until 1185, saw the rise of esoteric schools. These schools emphasized intricate rituals, mystical practices, and elaborate cosmological theories, distinguishing themselves from earlier traditions. For example, they incorporated detailed mandalas, which are featured in the exhibition, as central elements of their spiritual practices. Thirdly, both schools introduced a deeper level of belief through the use of detailed mandalas and ritual objects. The exhibition’s reconstructed immersive displays evoke the serene sanctuaries of Heian temples. Visitors will also encounter beautiful Buddhist sights that blends Buddhist cosmology with indigenous Shinto beliefs. Another turning point came with the Kamakura period, 1185–1333, when popular sects emerged, such as Pure Land and Zen. Pure Land Buddhism promised a way to enlightenment through simple devotional practices, while Zen emphasized meditation and self-discipline. The exhibition demonstrates, using artifacts, writings, and paintings, how these sects shaped Japanese spirituality. They emphasized simplicity, directness, and the natural world, which later influenced Japanese aesthetics. Finally, the Muromachi and early Edo periods (1336–1600s) confirmed that the teachings of Zen had found one of their most eager audiences among the Samurai class, attuned to its principles of attention, asceticism, and self-discipline. This exhibition will show visitors, through the exhibition, how Buddhism has adopted and changed throughout the ages and continues to play a big role in Japan’s culture and heritage.

Jake Hogan and Brandon O’Sullivan

Taima Mandala

This is an image of the 14th century Taima Mandala from Taimadera Temple and represents in great detail the Pure Land utopia from a sacred text wherein Buddha Shakyamuni leads Queen Vaidehi through meditative visualization to Amida’s Pure Land. The real Pure Land is at the center—a very beautiful paradise that conveys salvation and deliverance from suffering. On the left, Shakyamuni’s teaching to Queen Vaidehi reflects Pure Land Buddhism’s emphasis on led meditation; scenes on the right look at her journey and what she is instructed to imagine. Below, nine levels of birth in the Pure Land, each represents paths of spiritual progression.

This object aligns with the themes of the exhibition because Pure Land Buddhism is for all. Emphasizing a path to salvation directly through visual meditation, this tone made the unreachable truth of the teachings more tangible for simple believers. The levels of birth visualize the idea of spiritual progress achieved by one and all, aligning with the Kamakura-period Buddhist promise of hope and personal salvation during a time of social unrest. This connection between Heian and Kamakura Buddhism reflects a continuity in emphasizing salvation for the common people while adapting practices to suit the Kamakura period’s social and spiritual needs.

Visually, this work captures the Kamakura period’s artistic spirit through its detail and vibrant color palette. These elements invite the viewer into a compelling spiritual journey, embodying the exhibition’s theme of Buddhism as both an accessible and visually rich tradition.

Jake Hogan

Cleveland Museum of Art: https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1990.82

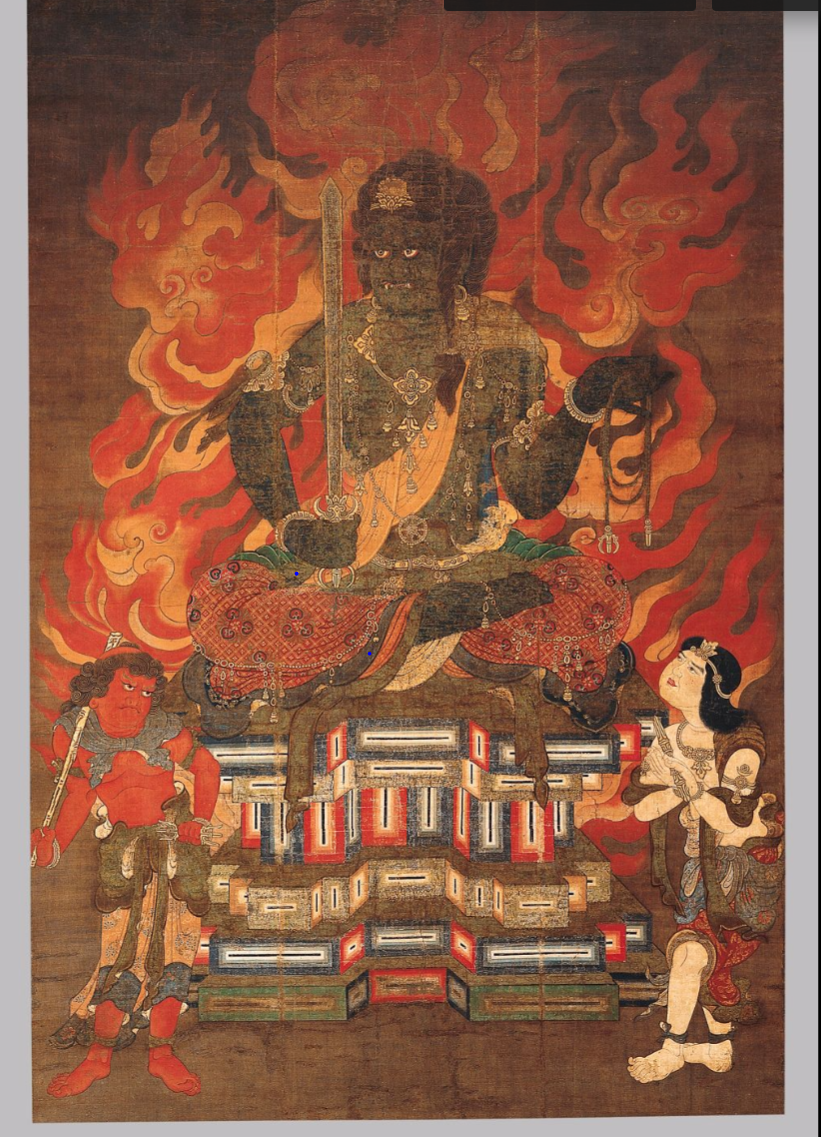

Achala Vidyaraja (Fudo Myo-o) with Two Attendants

This striking image of “Achala Vidyaraja, the Immovable Wisdom King,” reflects the powerful and protective nature of Japan’s Buddhist art in the late Kamakura period, 1185-1333. Buddhism reached Japan from Korea in the 6th century, influencing Japanese beliefs, art, and interactions with China and Korea. Achala is one of the five *Vidyarajas* or “Wisdom Kings” in Buddhist belief, each associated with a cosmic Buddha. Achala is the main character here, representing Vairochana, the Buddha of Boundless Light, who is for protection and wisdom. In this picture, Achala sits on a multilayer platform, encircled with fire, to show his fierce power in saving people from evil spirits. His blue body and a fierce expression show his power, while the sword and lasso in his hands denote his job of guarding and guiding believers. Elaborately designed, Achala wears a red robe with gold detail; his heavy full form and the detailed clothing reflect the artistic expression of late Kamakura Japan, while two little attendants stand beside him in devotion. This is an excellent example of Buddhist art from the 14th century in Japan, showing the deep existence and prevalence of Buddhism within Japanese culture now and in the past. Once housed at Jizoin temple, it stood as a testament to the profound depth of cultural exchange underlying early Japanese Buddhism.

Jake Hogan

Asia Society Museum: https://museum.asiasociety.org/collection/explore/1979-209-achala-vidyaraja-fudx014d-myx014dx014d-with-two-attendants

Miroku Bosatsu: The Future Buddha

This sculpture represents Miroku Bosatsu , the future Buddha who resides in the Tushita heaven, awaiting rebirth on earth to bring salvation to humanity. Miroku’s princely appearance and the symbolic stupa he often holds signify his role as a bridge between earthly suffering and the enlightenment to come. According to legend, the Indian philosophers Vasubandhu and Asanga of the Hossō sect received direct teachings from Miroku, further solidifying his importance in Buddhist cosmology. Buddhism, introduced to Japan in the 6th century, quickly gained traction, especially among the aristocracy, who were drawn to its promise of eternal salvation. The idealization of Miroku became central to this early devotion, with painted and sculpted images of him appearing in temple halls. This sculpture, with its refined features and meditative presence, reflects the grace and artistry of the period while serving as a focus for practitioners. The details of this piece suggest it dates to the end of the Kamakura period, as it predates the widespread use of shell powder beneath gold applications. It stands as a testament to the evolving artistic and spiritual traditions of premodern Japan, blending the profound philosophical roots of Indian Buddhism with the aesthetic sensibilities of Japanese culture.

Jake Hogan

Cleveland Museum of Art: https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1950.86

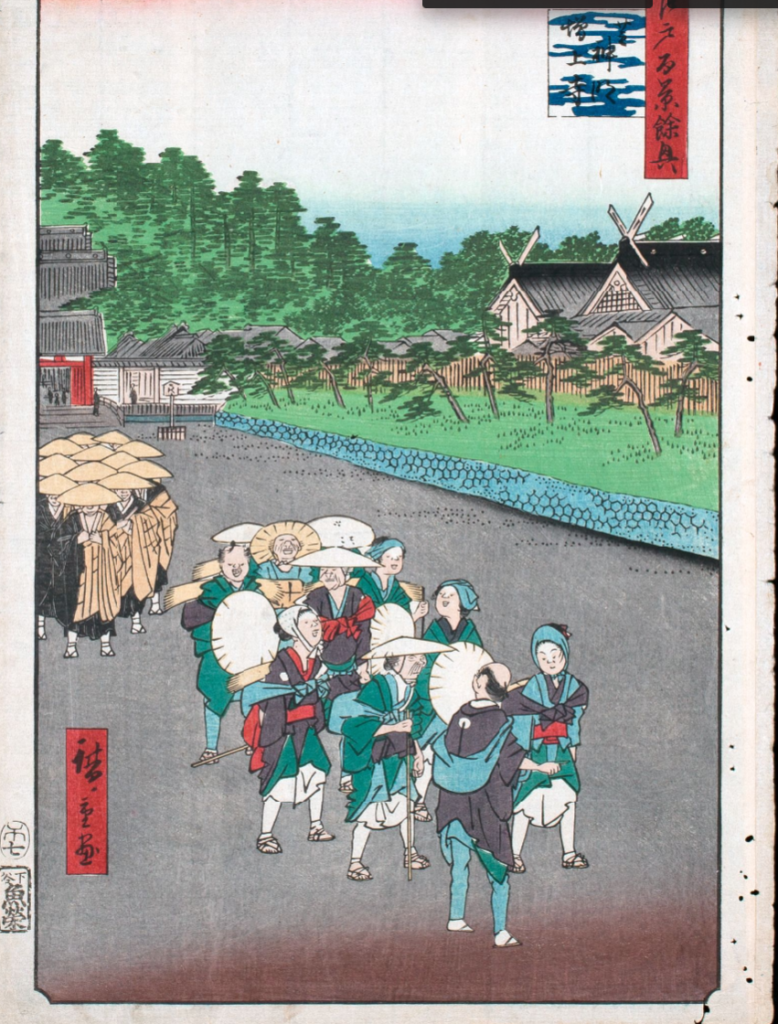

Shiba Shinmei Shrine and Zojoji Temple (Shiba Shinmei Zojoji)

This depiction by Hiroshige of Shiba Shinmei Shrine and Zōjōji Temple Combines the spiritual and everyday lives of pre-modern Japan, emphasizing the influence of Buddhism. This scene shows the cheerful visitors from the countryside who have just visited Zōjōji Temple, a central hub of Buddhist activity in Edo. As the burial site of the Tokugawa shoguns, Zōjōji Temple not only serves as a site for Japan’s most powerful rulers but also a training center for Buddhist priests showing Buddhism’s role in both governance and spiritual education. Behind the joyful tourists the monks stand in formation, their uniform attire reflecting the monastic life dedicated to Buddhist practices. They are preparing to beg in the streets each afternoon showing the Buddhist principles of humility and service, in contrast to the rural visitors. The coexistence of the monks and the regular people shows the prevalence of Buddhism in daily life. To the right, Shiba Shinmei Shrine complements the Buddhist elements with its roof beams and logs, symbolizing the architecture between Shinto and Buddhist traditions. Hiroshige captures the serene spirituality of Zōjōji Temple alongside the interactions of its devotees, offering a rich visual narrative of Buddhism’s evolution and its role in shaping Edo’s cultural and religious landscape.

Jake Hogan

St. Lawrence University: https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.27999509

Sinto Deity

Pictured above are two Shinto statues before the introduction of Buddhism to Japan. Brought primarily from Korea, the arrival of Buddhism in Japan in the sixth century brought a plethora of religious ideas, imagery, and customs that had had an immense and shocking impact on the Japanese people, who at the time already had a well-established belief system known as Shinto. Although Buddhism had a huge effect on the Japanese people, Buddhism was originally met with heavy resistance due to its Korean origins, and its likelihood to disrupt Shinto practices. At the beginning of its introduction to Japan, Buddhism attracted followers among Japan’s ruling class (mainly the Soga clan). The early adoption of Buddhism by aristocrats was the main driving force in allowing Buddhism to gain a foothold in sixth century Japan. Although some aristocrats supported buddhism, there were many aristocrats who resisted it, mainly due to a fear of losing influence. The rivalry between pro and anti-Buddhist aristocrats led to severe political strife, where Buddhism was used as a tool in the various clan conflicts that erupted, therefore complicating Buddhism’s acceptance. As well as its lack of acceptance, there were also numerous misunderstandings and misconceptions linked with Buddhism, primarily with the teaching of karma, reincarnation, and the notion of a “Pure Land”. The widespread confusion led to a widespread hindering of the adoption of Buddhism across Japan.

Brandon O’Sullivan

Cleveland Museum of Art: https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1978.3

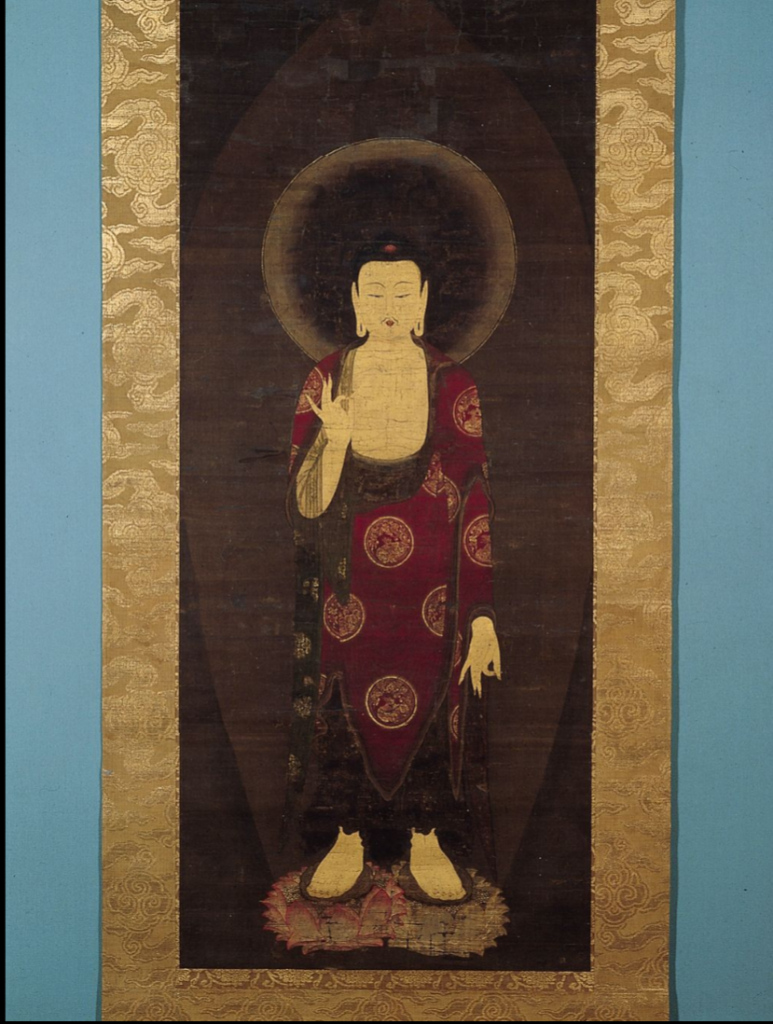

Descent of Buddha Amitabha (Amida Raigo)

Pictured above is the descent of Buddha Amitabha, a Buddha associated with boundless light and compassion. Amitabha was particularly central to Pure Land Buddhism, where he is referred to as “the Buddha of Infinite Light and Life.” Amitabha is known to have resided in a paradise known as the “Pure Land”, or Sukhavati, where people who devote themselves to Amitabha can be reborn through their faith and devotion. The painting shows Amitabha standing atop two lotus blossoms on a lotus pedestal, framed by a flame-shaped mandorla and halo. His upper garment is green with various floral decor, while his red shawl is decorated with roundels in gold leaf – a motif found in Korean, Chinese, and Japanese Buddhist paintings from the 9th to 14th centuries. As well as this, the painting portrays Amitabha as he descends to guide the deceased to rebirth in Sukhavati, or as mentioned earlier, the “Pure Land”, where the descent reflects his promise of presence to anyone devoted to rebirth in his “Pure Land”, the nineteenth of Amitabha’s forty-eight vows. This painting may have served along two other paintings that featured the bodhisattvas Avalokiteshvara and Mahasthamaprapta. The shift from Amitabha being surrounded by a heavenly assembly to simpler compositions with Amitabha alone or accompanied by only two bodhisattvas reflects the influence of the Chinzei branch of the Pure Land sect, led by Shokobo Bencho (1163-1238).

Brandon O’Sullivan

Asia Society Museum:https://museum.asiasociety.org/collection/explore/1979-191-amida-raigo-descent-of-buddha-amitabha/page/2

Buddha Amitabha

The introduction of Buddhism to Japan was undoubtedly one of the most important events in Japanese history, and had a long lasting effect on the development of its thought, art, and culture. Buddhism was introduced in the mid 500’s, either (538 or 552) from the kingdom of Paekche through a series of diplomatic exchanges that also led to an awareness of the beliefs and material culture of China and Korea. An interest in Buddhist pure lands, particularly Amitabha Buddha, developed in China in the 6th century, leading to a widespread worship of Amitabha during the Kamakura period (1185-1333). Amithabha’s descent from the Western Pure land is illustrated in the sculpture above (created in the 13th century). Amitabha is identified here by the position of his hands which are at the position of teaching or appeasement (vitarka mudra). In East Asia, this gesture is used to depict Amitabha during his descent to earth to guide a deceased practitioner to rebirth in his pure land, Sukhavati, which is sometimes known as the Western Pure Land. Images of Amitabha’s descent to earth illustrates the promise to appear at the moment of death to all individuals who desire to take part in rebirth in Amitabha’s Western Pure Land (a common theme in Buddhist practice). These vows are listed in the Sukhavativyuha, one of the principal texts of the Pure Land tradition. The versions of this theme that are painted and sculptured are known as descent of raigo images, which became popular in the 11th century, and are known to have been placed before the deathbed of a devotee in order to help her or him concentrate on Amitabha and his promise of rebirth to people who are devoted to him. In this sculpture, the rather mechanical treatment of the garment folds and the less fleshy depiction of the face, hands, and feet help date it to the third quarter of the 13th century. In this image, Amitabha stands on a lotus pedestal, and inlaid crystals are used to depict his eyes and the urna in his forehead. As well as this, he wears a skirt like garment and a long shawl, both of which were painted and then covered with designs in cut gold leaf, such as the floral roundels and leaf arabesques on the borders. Overall, the doctrinal basis of this development can be traced to the Treatise of the Selected Recitations of the Buddha’s Name of the Original Vow (Senchaku hongan nenbutsu), one of the most important works by Honen. In it, he states that single raigo images of Amitabha, or those in which he is attended by only two bodhisattvas, were more efficient because they focused the devotee’s attention more closely on the deity.

Brandon O’Sullivan

Asia Society Museum: https://museum.asiasociety.org/collection/explore/1979-204a-b-buddha-amitabha-amida-nyorai/page/5

Rokubu

Description:

The Rokubu was an itinerant Buddhist priest associated with the Ko-sodate-Jizo sect, which emphasized child-rearing and fertility practices. These priests were sought out by women facing infertility, as they were believed to possess the spiritual power to restore fertility and bless many families with children. The Rokubu would travel to many villages, offering prayers, rituals, and blessings to those who needed them.

An essential part of the rokubu’s practice was the portable altar that he carried on his back. This altar contained essential religious paraphernalia which included small statues of Jizo, sacred texts, and ritual objects. Jiza, a beloved bodhisattva in Japanese Buddhism, was said to be the protector of children, women, and travelers, making the rokubu’s role particularly significant for women longing to conceive.

During his visits, the Rokubu would perform ceremonies and recite prayers, invoking Jizo’s compassionate powers to aid those seeking his intervention. These priests played a vital role in rural communities across Japan, blending spiritual guidance with tangible hope for families that desired children. The practice reflects the deep connection between Buddhist faith and daily life in Japan, particularly in catering to addressing personal and communal needs. The Rokubu’s devotion and rituals illustrate the enduring appeal of Jizo’s compassionate imagery in Japanese religious culture.