By: Declan Newcamp and Luke Pickard

Buddhism was introduced to Japan in the mid-6th century and quickly became one of the most transformative influences in Japanese religious and political life. The height of its integration within the aristocrazy amongst Buddhism happened during the Heian Period as Buddhism adapted and evolved with Japan, blending its indigenous practices and shaping the dynamics of power, ritual and governance. In our virtual museum we will be highlighting through photos, artifacts and other things how the influence of Buddhism in the Jomon through the Heian period affected life in Japan and how it influenced religion and certain power dynamics throughout that time. Also we will be looking at certain rituals done by Buddhists to show their faith and religion.

The arrival of Buddhism occurred at a time when Japan was consolidating its political structures and examining their connections through Asia. Buddhism initially attracted the Japanese court’s interest due to its association with advanced cultures. This exhibition will show how during the Heian Period, Buddhism’s role evolved as new esoteric schools, these schools introduced complex rituals and teachings that appealed to the aristocracy, especially because they offered practices looked at as spiritually protective. This theme that regards Buddhism is interesting to study because as we know it started in the 6th century and still to this day, people around the world still practice Buddhism. Clearly the power and rituals they had were passed down. That is why we chose this theme, we wanted to learn more and inform the class what was done to make Buddhism so powerful.

Throughout the Jomon to Heian periods, Buddhism adapted to Japan’s cultural landscape, enriching its spiritual and political life. Rituals and teaching became a means for expressing authority, with rulers using Buddhist ceremonies to assert their legitimacy. Buddhism’s historical journey in Japan is not only one of spiritual growth but also a tale of political maneuvering with its religious structures and rituals profoundly influencing Japanese courtly politics and power dynamics across centuries.

Between the Kamakura (1185–1333) and Ashikaga (1336–1573) shogunates, Buddhism profoundly shaped Japan’s medieval society, blending spiritual practice with the complexities of courtly politics. During this period, Zen Buddhism gained prominence, introduced by Chinese monks, and flourished among samurai elites and aristocrats, offering a disciplined path aligned with the warrior ethos. Amid the intricacies of courtly life, Buddhist temples became centers of cultural and political influence, hosting elaborate rituals that reinforced the legitimacy of rulers and mediated divine favor. Key practices like meditation (zazen), sutra chanting, and intricate ceremonies not only embodied spiritual devotion but also underscored alliances between the religious and political spheres. This period witnessed the fusion of Buddhist thought with the arts, governance, and the fabric of daily life, leaving an enduring legacy on Japanese culture.

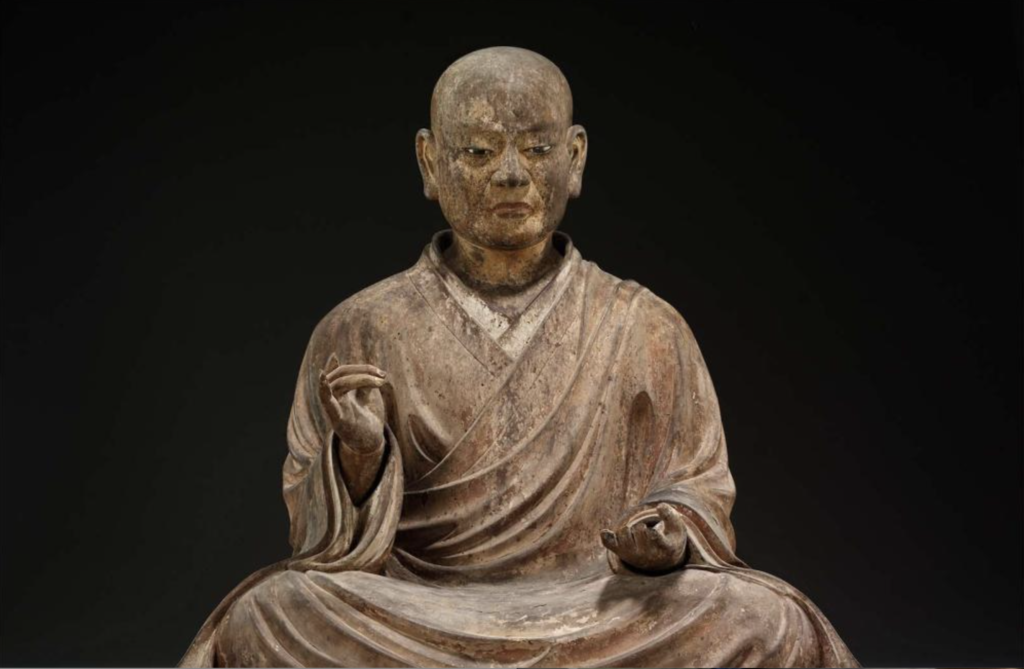

“The Shintō Deity Hachiman in the Guise of a Buddhist Monk” – Sōgyō Hachiman shin zazō

(https://collections.mfa.org/objects/18293)

The Shintō Deity Hachiman in the Guise of a Buddhist Monk (Sōgyō Hachiman shin zazō) is a fascinating example of the syncretism between Shintō and Buddhism that characterized much of medieval Japan, particularly during the Kamakura (1185–1333) and Muromachi (1336–1573) periods. This statue represents Hachiman, the Shintō kami (deity) of war and protector of Japan, depicted as a humble Buddhist monk. This blending of religious traditions highlights the interdependence of spiritual practices and courtly politics during Japan’s medieval period.

Hachiman’s identity as both a Shintō kami and a Buddhist figure reflects the shinbutsu shūgō (syncretism of kami and buddhas) that emerged in Japanese religious practices. Hachiman was widely venerated by the warrior class, especially the samurai, as a divine protector and a source of strength in battle. His association with Buddhism elevated his role from a local Shintō deity to a transcendent figure within the broader religious framework, allowing his worship to integrate seamlessly into Buddhist temple rituals.

The decision to depict Hachiman as a Buddhist monk is deeply symbolic. It conveys humility, wisdom, and spiritual authority, aligning with Buddhist ideals of enlightenment and moral conduct. This portrayal underscores the belief that Hachiman, as a protector of the nation, had transcended worldly concerns and embraced the universal truths of Buddhism. Such a depiction also reinforced the political legitimacy of the ruling class, as samurai and court officials could claim divine favor and moral superiority through their devotion to this dual-religious figure.

During the Kamakura period, the warrior class was rising in power, and Buddhism played a critical role in legitimizing their rule. Temples dedicated to Hachiman, such as the Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū in Kamakura, became centers of political activity and spiritual support for the samurai elite. By embracing both Shintō and Buddhist traditions, these temples fostered unity among Japan’s diverse religious and political factions, consolidating the power of the ruling shogunate.

The artistic style of the statue, with its serene expression and modest monk’s robes, reflects the aesthetic and spiritual priorities of the Kamakura period. Unlike earlier periods that emphasized grandiose depictions of deities, Kamakura art sought to humanize divine figures, making them more accessible to worshippers. This realism resonated deeply with the samurai class, who valued practicality and discipline, both on the battlefield and in spiritual practice.

In courtly politics, this image of Hachiman served as a potent symbol of the emperor’s divine authority and the shogunate’s military dominance. The duality of Hachiman as a Shintō deity and a Buddhist protector underscored the unity of spiritual and temporal power, reinforcing the notion that Japan’s rulers governed with divine sanction. The statue’s existence within temples connected to the imperial court and the shogunate further emphasized the integration of religious devotion and political strategy.

In summary, The Shintō Deity Hachiman in the Guise of a Buddhist Monk represents the intricate interplay between religion and politics in medieval Japan. Through its blending of Shintō and Buddhist elements, the artwork embodies the fusion of spiritual traditions and the political dynamics of the time, serving as both a religious icon and a statement of authority.(Written By Luke Pickard)

“Taranatha’s Vision of Shakyamuni’s Quest- Andrew Quintman and Kurtis R. Schaeffer

( https://rubinmuseum.org/projecthimalayanart/essays/a-monumental-life-of-the-buddha-mural/ )

The article Visualizing the Story of the Buddha explores the rich visual and narrative tradition surrounding the life of Buddha, particularly in Tibetan Buddhism. It highlights the monumental mural at Puntsok Ling Monastery, which visually chronicles Buddha Shakyamuni’s journey from prince to enlightenment. Spanning 277 feet, this 17th-century mural was commissioned by the Tibetan teacher Taranatha, who wanted to depict the Buddha’s life in a way that emphasized his interactions with the world rather than just his transcendent state. The mural illustrates key moments from Buddha’s life in a sequence of complex, layered images that require viewers to move through space to fully absorb the story. It begins with Buddha’s realization of human suffering—symbolized by encounters with aging, sickness, and death—which inspired his departure from royal life. The scenes progress through his spiritual journey, battles with demons, and eventual enlightenment, showing him in diverse landscapes interacting with gods, demons, and ordinary people. Taranatha’s design uniquely focuses on Buddha’s travels and teachings, emphasizing his connections with society and his role as a compassionate, relatable figure. This perspective contrasts with traditional representations that often depict Buddha as a distant, serene deity. The mural’s format not only draws viewers into the Buddha’s life but also embodies a teaching tool, using repetition and movement to guide understanding of Buddhist teachings. Through this mural, Taranatha aimed to make Buddhism accessible and human, emphasizing the Buddha’s continuous engagement with the everyday world as a source of spiritual insight. (Written By Luke Pickard)

“Hossō Mandala” – Unknown

(https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/57172)

The bodhisattva sits on a lotus throne, symbolizing spiritual purity and detachment from worldly concerns, and is surrounded by radiant halos signifying enlightenment. Below the central figure, rows of monks or disciples are depicted in a hierarchical arrangement, emphasizing the transmission of Buddhist teachings from the divine to human followers. This composition underscores the bodhisattva’s role as a mediator between the transcendent and the mortal realms.

During the Muromachi period, Buddhism, particularly Zen and Esoteric practices, played a vital role in courtly politics and cultural production. Temples and monasteries were not only spiritual centers but also hubs of political influence, patronized by the shogunate and samurai elites. By commissioning and displaying artworks like this, political leaders demonstrated their piety and legitimacy while fostering alliances with powerful religious institutions. The artwork’s intricate detail and vibrant imagery also reflect the refined aesthetic sensibilities of the time, shaped by Buddhist principles and supported by aristocratic patronage.

This painting may have served multiple purposes: as a devotional object for meditation, a visual aid in ritual practice, and a symbolic assertion of the political elite’s alignment with divine authority. The inclusion of disciples below the central figure reflects the hierarchical structure of both Buddhist monastic orders and the feudal political system of the Muromachi era. Just as the bodhisattva guides and protects followers, the ruling class sought to position themselves as moral leaders under divine protection.

Furthermore, the central theme of compassion and salvation resonated deeply in a time of political instability and civil war. By invoking Buddhist ideals of harmony and spiritual protection, artworks like this reinforced the ruling class’s role as custodians of both the physical and spiritual well-being of the nation, bridging the realms of governance and religion. This piece, therefore, embodies the deep interconnection between Buddhism and courtly politics in medieval Japan. (Written By Luke Pickard)

Kano Hideyori, d. 1577. Maple Viewing at Takao. n.d. Gold and paint on paper. https://jstor.org/stable/community.13573603.

Towards the end of the Heian era there lead to the creation of a new art form. This new art form was llustrated, horizontal narrative that came in the form of a scroll. This is an example of an Emaki scroll. Emaki scrolls are famous for showcasing two distinct artistic styles: onna-e (women’s pictures) and otoko-e (men’s pictures). These styles were designed to appeal to different tastes—onna-e often dealt with romantic or courtly themes, while otoko-e focused on battles or historical events. The differences between these two styles give us insight into the gendered preferences and cultural values of the time. This is an example an onna-e picture. The people in this emaki are in traditional clothing commonly worn during the Heian era. It focuses on beauty, nature, and courtly life. The scroll as you unfurl it and see more and more feels like the passage of time and the changing of seasons. It embodies koyo- the appreciation of changing leaves, which invites the viewer to a peaceful moment of enjoying the natural beauty of the world. The primary and vibrant colors of red, green, blue all draw your attention to different parts of the art as you unfurl it and see more of it.

attributed to Tensho Shubun (active 1st half of the 15th century). Painting Titled Landscape in the Evening Glow. early 15th century. Paper; ink and color. Kosaka Family Collection, Tokyo, Japan. https://jstor.org/stable/community.14402848.

In this artwork it portrays buddhist temples. The black and white brushstrokes reminds you of peacefulness and serenity of twilight and night. It also like the previous one is focused on portraying beauty in nature and in the structures of society. Instills within the viewer a sense of peace and comfort. In the right side of the painting there’s a bridge with two people on it. There’s a part of the temple hidden in the trees on the right side with mountains in front of and behind it that draws your attention to it. There are boats flowing in the water surrounding the temple with some fishermen on the boats. This is to make it more accurate to reality and makes it connect with the viewer more. It allows you to see average people in the setting in a profession that is very common. It feels like an encapsulation of the fleeting beauty of the world before the world falls into night (death). It shows our limited time on earth and how beautiful is is. Day to night is a common theme in japanese art. As day and night are intertwined and celebrated for impermanence like life is too short. (Written by Declan Newcamp)

attributed to Tensho Shubun (active 1st half of the 15th century). Painting Titled Landscape in the Evening Glow. early 15th century. Paper; ink and color. Kosaka Family Collection, Tokyo, Japan. https://jstor.org/stable/community.14402848.

Declan Newcamp

In this artwork it portrays buddhist temples. The black and white brushstrokes reminds you of peacefulness and serenity of twilight and night. It also like the previous one is focused on portraying beauty in nature and in the structures of society. Instills within the viewer a sense of peace and comfort. In the right side of the painting there’s a bridge with two people on it. There’s a part of the temple hidden in the trees on the right side with mountains in front of and behind it that draws your attention to it. There are boats flowing in the water surrounding the temple with some fishermen on the boats. This is to make it more accurate to reality and makes it connect with the viewer more. It allows you to see average people in the setting in a profession that is very common. It feels like an encapsulation of the fleeting beauty of the world before the world falls into night (death). It shows our limited time on earth and how beautiful is is. Day to night is a common theme in japanese art. As day and night are intertwined and celebrated for impermanence like life is too short. Declan Newcamp

Scene from the Life of the Buddha | Japan | Muromachi period (1392–1573) | The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (n.d.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45209

This painting shows a blend of traditional Buddhist themes along with aesthetics that were very influential at the time. The Kamakura period, otherwise known as the Muromachi period, was a time of the great rise of Zen Buddhism and Japanese ink painting, which they utilized to convey spiritual depth through simplicity and restraint. In this particular painting, the scene shows significant moments from the life of Buddha, including his birth, his enlightenment, and his first sermon. The focus is on the symbolic elements rather than realism, with flowing brush strokes and minimal color to highlight the spiritual essence of the moment. It also does this to make it seem more fantastical and superhuman. This painting style, which is made to emphasize harmony, balance, and ethereal quality, has much more simplified and abstract figures with an emphasis on the posture to communicate the Buddhist divine serenity and his enlightenment. They include natural elements such as trees, water, and clouds, but these are much more stylized in a meditative way to enhance the spiritual atmosphere. The minimalist approach and subdued color palette encourage contemplation in line with the Zen principles, which were in the middle of a very big breakout opportunity in this time period.

Ukita Ikkei | Tale of a Strange Marriage (Konkai Zoshi) | Japan | Edo period (1615–1868) | The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (1858, January 1). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/44854

Declan Newcamp

This art piece is a woodblock print that gives a surreal depiction of Japanese literature. It’s a satirical piece in that it’s animals that are getting married in this, and yet all of the things portrayed within the painting outside of the actual animals and the humans in this woodblock print are accurate to the period. It’s a fascinating piece; it’s one of the most accurate depictions of the nobility in courtly rituals that you could find at the time while still being a satirical piece. Satirical not just in that the humans are replaced with foxes but also in the poses, gestures, and expressions that the characters are doing within the piece itself. So, it’s both an unusual marriage between boxes and an unusual marriage between art forms and history. In that “unusual marriage,” where history is accurately represented and yet also being fun at the same time, and the culture is accurately represented and yet made fun of at the same time. So it is a very effective choice to be chosen as a famous Japanese art piece in that you are able not just to get a glimpse at the nobility and the courtly rituals; you’re also able to get a glimpse into the literature and culture of the time. This art piece captures not just the everyday life of the courtly rituals of the nobility; it also captures a lot of the darker, more fantastical elements of Japanese culture.

“Standing Buddha”

(https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/667003)

This wooden sculpture, titled Standing Buddha, dates from the Heian period (794–1185) and is part of the collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. It represents the growing influence of Buddhism in Japan during the transition from the Jōmon period to the more centralized and sophisticated Heian period. The figure embodies simplicity and serenity, characteristic of Heian-period Buddhist art, reflecting the spiritual ideals of enlightenment and compassion.

Buddhism, introduced to Japan from the Korean peninsula and China in the 6th century, became a central element of courtly rituals and politics by the Heian period. The Standing Buddha sculptures often served as focal points for religious ceremonies, intended to invoke divine protection and promote harmony within the court and broader society. These rituals, supported by the imperial family and aristocracy, aimed to consolidate power by associating rulers with Buddhist ideals of moral authority and divine favor.

The unadorned elegance of this sculpture suggests its purpose was deeply spiritual, emphasizing meditation and the detachment from material concerns central to Buddhist practice. It also reflects the integration of Buddhist philosophy into the aesthetic values of the court, blending religious devotion with political legitimacy, making it a vital symbol of Heian-era governance and cultural identity. (Written by Luke Pickard)