By: Bryce Ferrell and Chase Jordan

Introduction:

Our exhibition, The Feminine Spheres of Early Japan, explores women’s nuanced roles and influence in the Japanese archipelago from the Heian period through the medieval period spanning the Kamakura to the Edo periods examining their positions in public and private spheres . In early Japan, women held complex roles that were seen as both large and small. Our exhibition focuses on the ways women navigated societal expectations, self-expression, and ways in which they impacted cultural and political landscapes within a male-dominated system. Our focus is on understanding the lives of prominent women such as the deity Queen Mother of the West and Murasaki Shikibu who served as figures of feminine influence for both spheres, showcasing how women shaped early Japanese history through power and literature. As Japan transitioned into a warrior society during the Kamakura period, women in samurai households managed estates and family affairs while their male counterparts were engaged in military campaigns. This marked a shift in their roles as they adapted to the new socio-political landscape.

During the Heian period, women experienced a decline in formal political roles compared to earlier periods as Confucian ideals began emphasizing a male-dominated hierarchy. However, women did not back down as they continued to establish influence within the imperial court of the private sphere. Whether they acted as regents, advisors, or key figures in courtly succession, women did not get discouraged when they were excluded from public politics. In the Heian period, the birth of noblewomen allowed women to flourish their influence through literature and arts. The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu is a good representation of the aesthetic ideals of court life as it showcased women’s creativity and intellectual influence. In the medieval period, the cultural landscape shifted further. Religious movements like Zen Buddhism and Pure Land Buddhism opened new avenues for women’s participation in spiritual practices and artistic expression. Women’s roles extended beyond court life as many engaged in labor, artisan production, and other economic activities that contributed to Japan’s evolving economy. Simultaneously, women in warrior households continued to influence family dynamics and local governance.

Although women may not have held titles as rulers or warriors as the men who often overlooked them, they left a profound mark on Japan’s history. From spiritual practices to artistic expression, their contributions demonstrate a balance between public authority and private wisdom. Even in the Edo period, women’s influence persisted through cultural traditions like wabi-sabi and yūgen which emphasized simplicity and imperfection as well as through poetry, Noh theater, and domestic roles. Through their subtle yet impactful roles in poetry, Noh theater, and religious life, they left enduring legacies. By examining these spheres of influence as reflected in the images below, our goal is to offer a better understanding of how women navigated and shaped premodern Japanese society.

Images/Paintings/Prints/Scrolls:

Murasaki Shikibu (Lady Murasaki)

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14536001

This hanging scroll is of Murasaki Shikibu sitting down writing in what is likely to be a private room of the Heian court. It perfectly represents the contrasts between the private and public spheres of Japanese women during this period. While Murasaki belongs to the private sphere in this scroll, her impact was felt throughout the public sphere. Her work such as The Tale of Genji circulated within aristocratic circles and helped shape court culture. As for the scroll itself, it’s important to recognize her belonging within the private sphere of the Heian court. She is depicted as secluded and away from everyone else as she gazes out into nature with beautiful trees, a body of water, and ultimately a view worthy of being separated from the outside world. A taste of what Heian aristocracy was like during this period. In Heian Japan, noblewomen of the court like Murasaki would dedicate their lives to writing within the private sphere as they were not directly associated with the formal structures of Japanese public governance. However, these women held significant cultural influence. For example, Murasaki’s incredible work of the world’s first novel titled The Tale of Genji provides insights into the narrative and emotional depth of Japanese literature. Her work exemplifies the Heian period’s aesthetic of “mono no aware” which is a term that describes a sensitivity to ephemerality, a poignant appreciation of the transient beauty of things, and evokes a gentle sadness as it is realized that these moments cannot last. Maybe the scroll here is of her writing The Tale of Genji. The work of women like Murasaki in the Heian court are examples that showcase the importance of their perspectives as their voices, at the time, were often underrepresented in the public and political spheres. While these women may not have held official positions of authority, their influence persisted through their creative and intellectual contributions which offered invaluable perspectives on Heian society.

Written by Bryce Ferrell

Queen Mother of the West

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5555/individual.b5231564-07e6-4ef3-976a-4fa5daa46143

The painting represents the Queen Mother of the West, a central deity in East Asian mythology who symbolizes immortality, wisdom, and power. Revered throughout China and Japan, this subject in early Japanese art depicts the cultural ideals concerning women in spiritual and divine authority positions. Queen Mother instills regal poise, clothed in layered, flowing robes that emphasize her status. Standing beside the young female attendant, she combines both a tranquil, composed appearance of grace and strength in her placid expression. This shows how important famine figures were in early Japan. The setting, developed with elements like a twisted pine tree and bamboo, reinforces themes of resilience, longevity, and harmony with nature, which are closely associated with her role as a guardian of life. Early Japan had female deities, such as the Queen Mother of the West, who symbolized something other than beauty; she was a force—one both powerful and nurturing—that was indispensable to the cosmic order. The piece mirrors some early times when the image of women in power, particularly spiritual, was at the center of the cultural narrative. For example, the powerful Queen Himiko and Empress Suiko. With such a commanding female figure illustrated, the painting offers insight into how early Japanese society revered the role of women as pivotal figures not only spiritually, but within the spheres of early Japanese politics.

Written by Chase Jordan

Zuihoin at the Daitokuji Zen temple complex

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14378791

This image of a Zen garden depicts what it would look like during the Muromachi period. This was a critical time during the Ashikaga shogunate when Zen Buddhism flourished as a cultural and spiritual force in Japan. The arrangement of rocks, sand, and moss represents an abstract natural landscape that was designed to encourage meditation. The raked patterns in the gravel symbolize rippling water, while the stones evoke islands or mountains. These elements emphasize simplicity, balance, and nature which are key characteristics of Zen philosophy. Zen gardens, like this one, were often associated with Buddhist temples and became centers of spiritual practice during the medieval period. Women engaged in Zen practices in private spaces and found avenues for spiritual expression and reflection despite being excluded from public religious leadership such as being nuns, lay practitioners, and patrons of temple construction and maintenance. These gardens also connect to broader cultural aesthetics of the time, including wabi-sabi and yūgen, which emphasized beauty in simplicity and imperfection. This garden ultimately reflects women navigating the public and private spheres, as it symbolizes the inner, contemplative world where women could assert spiritual autonomy. Historically, these Zen spaces offered them opportunities to cultivate their spiritual identities through commissioned artwork and poetry that were integral to religious life. Despite societal restrictions, their engagement with Zen practices as nuns, patrons, and meditators contributed to preserving and shaping the aesthetics and spiritual traditions of early Japan. By focusing on meditation and self-discipline, Zen gardens represent the enduring influence of spiritual and artistic contributions on Japanese cultural history. This demonstrates how women in medieval Japan played a significant role not only in their spiritual lives but also in Zen ideals and aesthetics.

Written by Bryce Ferrell

Bijin Junikagetsu (Beauties in the twelve months): March

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.27018128

This image reflects the social and cultural roles of women in early modern Japan, in their centrality to foster leisure, community, and domestic harmony. The scene shows women in a garden, playing in nature and with each other, most likely celebrating a season. Such settings highlight the importance of seasonal observances and rituals to which women often took leading roles in organizing and participating in these culturally significant events. The bright kimonos and elaborate hairstyles reflect the importance of aesthetic expression and refinement that are central to women’s roles in society, particularly among the upper classes. Women were expected to continue these traditions in the home, balancing beauty and decorum as they oversaw domestic and social concerns. Many of their activities revolved around the creation of a nurturing and orderly environment, from the hosting of tea gatherings to the maintenance of familial and community ties. This image also captures the duality between nature and femininity, reinforcing traditional Japanese ideals that link women to the cycles of life and seasonal beauty. The relaxed yet graceful postures of the women stress their role as cultural and emotional anchors within both family and society. This depiction underlines how women’s contributions extended beyond domestic labor to the preservation and embodiment of cultural values.

Written by Chase Jordan

Tomoe Gozen Killing Uchida Saburo Ieyoshi at the Battle of Awazu no Hara

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.18678270

This print depicts Tomoe Gozen, who was a Onna-Bugeisha, a female warrior active during the Heian period through the Tokugawa period. Tomoe Gozen is seen mounted on a horse with a full set of armor in the act of slaying Uchida Saburo leyoshi during the Battle of Awazu no Har. This battle took place in 1184 during the Genpei War which was between the Taira and Minamoto clans. Tomoe Gozen fought under Minamoto no Yoshinaka, a powerful leader during the Genpei War and her bravery and skill in the war solidified her status as one of Japan’s legendary warriors. It’s interesting to see the intricacy of the armor she is wearing and the intensity of the scene as it highlights her significance as a female warrior in a predominantly male scene. This print is particularly important to the strength and skill of women as she defies societal norms that typically relegated women to the domestic or private spheres. Though female samurai were rare, they played pivotal roles in shaping Japanese society during times of conflict because men typically engaged directly in warfare. This portrayal emphasizes the fluidity of women’s roles as they ranged from warriors on the battlefield to managers of estates and cultural preservers during the Tokugawa period. Women in samurai households managed estates and oversaw finances while the men engaged in public governance or the military. Tomoe Gozen served as a reflection of cultural nostalgia of the Tokugawa period as a heroic figure for women of the Edo period, who’s roles were restricted, and gave them hope. Overall, this print highlights Tomoe Gozen’s lasting legacy as a figure of female strength in the Heian period.

Written by Bryce Ferrell

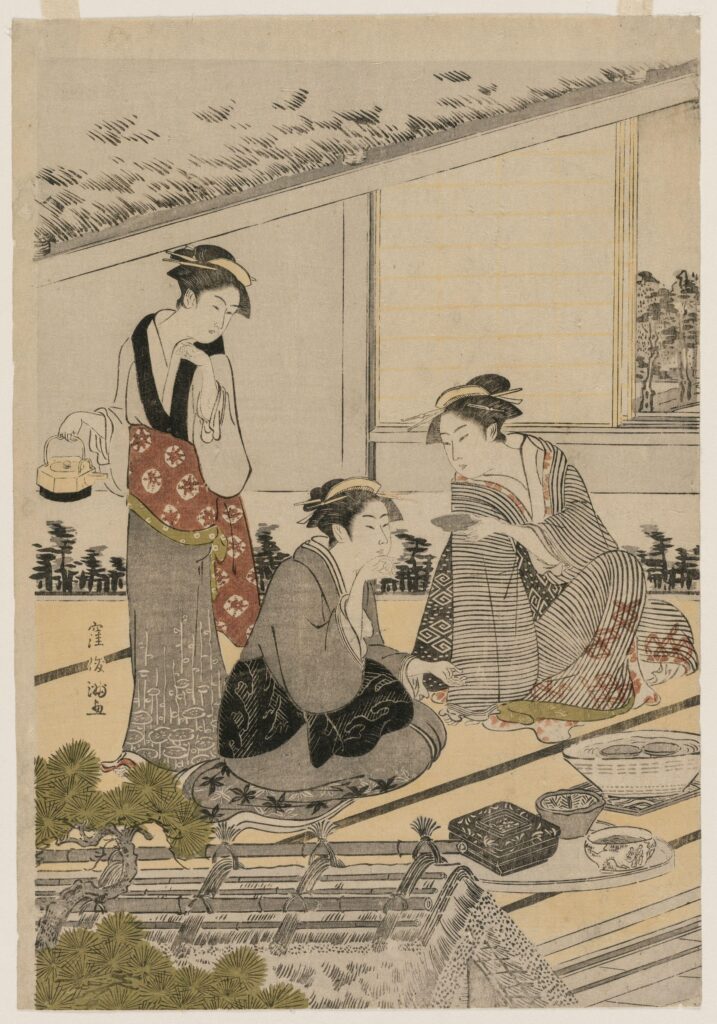

Women in a Tea House

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.24585558

This print offers a glimpse into the private lives of women during the Edo period in Japan, specifically within the setting of a tea house. The scene captures three women engaging in a quiet and intimate moment while enjoying tea and conversing. The subtle details such as the outdoor view through the open window reflect both the tranquility of the scene and the sophisticated cultural practices. The tea house itself is a central symbol of cultural life during the Edo period where the principles of wabi-sabi emphasize simplicity, impermanence, and the appreciation of beauty in everyday life. The elegant and graceful women in the scene are courtesans and their roles were to be both participants and preservers of the refined cultural aesthetics of the Edo period. Courtesans were highly skilled entertainers and artists who were great in tea ceremonies, poetry, calligraphy, and music and they were not only symbols of beauty, but they also played an intellectual and cultural role within Edo society. This scene captures the intersection of women navigating the private and public spheres as tea ceremonies were both intimate personal rituals that provided quietness and mindfulness and culturally significant practices that showcased artistry. The role of women in tea houses and cultural spaces during this era also reflects the limitations imposed by Confucian ideals that emphasized male dominance[MOU5] . Under Confucian ideals, women’s roles were confined to domestic spaces but courtesans found a unique position within the private sphere. By actively participating in practices such as tea ceremonies, these women not only preserved traditional aesthetics but also contributed to the cultural movement during their time.

Written by Bryce Ferrell

History of Kamakura

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.18678926

The period between 1185 and 1573 saw a complete turn in the social position of women and their reflection in Japanese art. Under the new feudal government, the status of women sank noticeably from the heights achieved during the Heian period; female writers were becoming few and far between in literature. This dramatic change reflected broader societal transformations with the capital’s move to Kamakura and martial discipline replacing the refined court culture which had earlier lifted women’s artistic and literary contributions. Though women in the merchant and artisan classes maintained some economic independence through running businesses, brewing sake, and managing financial operations, their courtly counterparts saw their influence wane. The artistic depictions of women during this period often came in yamato-e paintings, which employed certain stylistic conventions, including stylized figures with abbreviated facial features and the use of rich pigments. Such paintings often illustrated classical tales from the earlier Heian period and thus preserved memories of a time when women held greater cultural authority. Dragons in Japanese art of this period generally represented water deities associated with rainfall and bodies of water, rather than symbols of feminine power. This era’s artistic production reflected this changing social dynamic, as most prestigious artistic positions, such as those in the Tosa School serving the imperial court, were held by men. The period represents a complex transition in Japanese society where the economic roles of women remained vital in certain sectors, while their cultural and artistic influence was in decline under the new warrior-dominated social order.

Written by Chase Jordan

Yuagari, Kansei koro fujin. (After the bath: Woman of the Kansei era). From the series Thirty-six elegant selections.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.27018129

It captures women’s important place in domestic life during Japan’s Edo period (1603-1868) and brings forth the core of harmony and tradition within the household. The serenity of the scene-a woman drying herself after a bath-suggests an emphasis on cleanliness and ritual in domestic spaces. Women’s tasks went beyond the physical; they also maintained cultural practice and fostered refinement and order. They were entrusted with household management, the upbringing of children, and ensuring that the daily running of a home was well-oiled to keep social and familial continuity going. The delicacy of the patterns and the colors in her attire speak to the aesthetic sensibilities of the time, as often women’s dress and activities did. Women also represented the moral and emotional center of the family, with their patience, care, and diligence being ideals. Domestic life, often overlooked in historical narratives of samurai and politics, was the foundation upon which societal order was built. It shows, in the understatement of elegance and routine, a way in which women at that time maintained traditions and values at home and in family life to ensure family and community stability during the Tokugawa period.

Written by Chase Jordan